Revista Produção e Desenvolvimento, v.5, e364, 2019

DOI: https://doi.org/10.32358/rpd.2019.v5.364

TOURISM, HOTEL MANAGEMENT AND SOCIO-ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT IN THE DEVELOPING WORLD: COUNTY OF INHAMBANE, MOZAMBIQUE

|

Orlando Alcobia12,1* 1. Universidade Eduardo Mondlane, Inhambane – Mozambique 2. Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, 59066-800, Natal – Rio Grande do Norte, Brasil.

|

|

|

Article submitted in 21/10/2018 and accepted in 08/02/2019 |

|

ABSTRACT

This article aims to analyze the hotel units’ operational practices in Inhambane, assesses their socio-economic impacts into the local community and proposes hotel operations qualitative measures to promote sustainable socio-economic development. Follow the Quivy and Campenhoudt methodological model for social sciences and has the hotel units and their workers as objects of study. Presents the following dimensions: hotel operations multiplier effect, the employability quality generated by them, their contribution to the welfare infrastructures and their environmental policies. Remarks that the implemented hotel development model is based on a neoliberal matrix, mostly in result of foreign or multinational investments, not guaranteeing a significant multiplier effect in the local economy, its job offer quality is often precarious, unable to have a significant contribution to the local "welfare" infrastructures improvement and sometimes producing undesirable environmental costs. Concludes that it is pressing to rethink the whole model of tourism development in Inhambane, retaining in its territory the economic benefits of the touristic activities and transforming the local community in its main beneficiary.

|

KEYWORDS: hospitality; tourism; development; local community. |

TURISMO, GESTÃO HOTELEIRA E O DESENVOLVIMENTO SOCIOECONÔMICO NOS PAÍSES EM DESENVOLVIMENTO: MUNICÍPIO DE INHAMBANE, MOÇAMBIQUE

RESUMO

Este artigo visa analisar as práticas operacionais das unidades hoteleiras no Município de Inhambane, avalia os seus impactes socioeconómicos no seio da comunidade local e propõe medidas qualitativas de operações hoteleiras que promovam um desenvolvimento socioeconómico mais sustentável. Segue o modelo metodológico preconizado por Quivy e Campenhoudt para as ciências sociais e tem como objetos de estudo as unidades hoteleiras e os seus trabalhadores. Apresenta as seguintes dimensões em análise: o efeito multiplicador das operações das unidades hoteleiras, a qualidade da empregabilidade gerada pelas mesmas, o seu contributo para a melhoria das infraestruturas de “bem-estar” e as suas políticas ambientais. Observa que o modelo de desenvolvimento hoteleiro implementado é assente numa matriz neoliberal, na sua maioria fruto de investimentos estrangeiros ou multinacionais, não garantindo um efeito multiplicador de relevo na economia local que carece de tecido produtivo, sendo a qualidade da sua oferta de emprego muitas vezes precária, não conseguindo contribuir de forma significativa para a melhoria das infraestruturas de “bem-estar” locais e produzindo por vezes custos ambientais indesejáveis. Conclui que se deve repensar o modelo de desenvolvimento turístico do município, retendo-se em Inhambane os benefícios económicos das atividades turísticas praticadas no seu território e transformando a comunidade local no seu principal beneficiário.

|

PALAVRAS-CHAVE: hotelaria; turismo; desenvolvimento; comunidade local. |

1. INTRODUCTION

Tourism is seen by most government entities as an opportunity window for their countries’ socio-economic development. Due to its galvanizing character, it invariably results in the leverage of many other supporting economic activities, such as construction, trade, transport, telecommunications or agriculture. For Krippendorf (2003), De Pieri and Panosso Netto (2015), Czaika and Neumayer (2017), Song et al. (2018) and Javid and Katircioglu (2017), tourism activities undoubtedly leverage the economy by attracting foreign investments, fostering local employability, business turnover, tax revenues, stimulating the people displacement and the belonging to a global society sense, raising awareness for environmental preservation and promoting the technology dissemination. Thus, the focus on tourism development has economic, social, political, cultural, ecological and technological repercussions.

If the focus on tourism is now global, the developing countries are the most dependent on this economic activity, because according to the WTTC (2018) they have the highest percentage of the tourism sector contribution in their respective Gross Domestic Product and in their employability rates. Sharpley and Telfer (2008), Hrubcova et al. (2016) and Rivera (2017) state that especially in these countries tourism becomes essential by attracting foreign currency, fighting poverty, increasing exports, promoting and maintaining peace or enhancing local culture. However, because of the economy' scarce diversity and less regulatory power of the states, the negative tourism impacts in these countries are also amplified. The same authors refer that, sometimes, tourism potentiates economic leakages, increases social inequalities, destroys the environmental patrimony and causes cultural shocks.

Included in the tourism' sphere, there are different activity sectors such as transport, tour operators, travel agencies or leisure service providers. However, one of them has special relevance: the hotel industry.

The United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), in its report entitled Tourism - Industry as a Partner for a Sustainable Development (2002), considers the hotel industry the main player in the tourism sector. Ajake (2015) also praises its high capacity to create jobs and its extensive contribution to the countries’ GDP, derived from the tax revenues that produce as well as the indirect jobs that promote. From this perspective, the hotel industry has crucial importance for developing countries that make tourism a central focus for their socio-economic rise and see in its vitality a driving force behind various infrastructures.

However, the hotel industry implementation in developing countries must be monitored with a high rigor degree by regulatory authorities, because its high investment cost comes mainly from foreign investments. The WTO (2013, p.72) in its guide entitled Sustainable Tourism for Development warns that this type of investment has some disadvantages, namely "dependency on investment decisions taken externally and a potential for higher economic leakage". ILO (2010) considers that despite the fact the hotel sector is a huge employer sector, its wage practice is often below the national averages and is also characterized by some precarious working conditions.

Thereby, the socio-economic benefits for the host communities are highly dependent for the hotel units' management strategies and their capacity to ensure a healthy local workforce involvement, promoting a fair economic benefits redistribution of their operations, as directly as indirectly. In this perspective, Liu and Li (2018) note that "sustainable development of tourism in developing economies may require greater community involvement".

Analyzing the panorama of one of the most prominent tourism ex-libris of Mozambique, the Inhambane County, comes across with the inconsistencies in the document entitled Strategic Plan of Inhambane Province 2011-2020 belonging to the Government of Inhambane Province (2010). In it, tourist activity is seen as a priority because it is a fundamental element for the development being considered an opportunity and a strong point. However, and despite the fact that the Inhambane County is nowadays a consolidated tourist destination in Mozambique, the same document reflects that the Inhambane’ Absolute Poverty Indexes exceed those of the national average.

It seems evident that, in the County of Inhambane, the tourism development in general and hotels, in particular, are not proving to be up to the task of catapulting the local population living conditions to levels consistent with the status of their territory in the tourism scenario.

In this case, it is pertinent to recall the words of Jafari (2018): “Tourism is to make a city better for its people, a principle that should never escape us. (…) A nice place to live is a nice place to visit, this is a win-win strategy!”

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study was guided by the Quivy and Campenhoudt (2005) proposed methodological model, designed for studies focused on the scientific area of social sciences.

Since socio-economic development is heterogeneous in its unicity because it is composed of several interest areas, this study analysis model was based on four dimensions: social, economic, infrastructural and environmental.

Therefore, four hypotheses were also tested this study:

- Hypothesis 1: The Inhambane County hotel units implement operations leading to the existence of an economic multiplier effect that expands to other economic activities of the county.

The studied indicators were the local suppliers' usage, the choosing suppliers criteria, the local companies services hire, the local art and culture events supported and the used ways to encourage guests to get involved in community activities.

- Hypothesis 2: The employability generated by the Inhambane County' hotel units contributes satisfactorily to the county socioeconomic development.

Indicators such as job satisfaction, wage level, extra-wage benefits, the opportunity to benefit from professional training, career progression prospects, empowerment given to workers and equal opportunities for management positions were measured.

Hypothesis 3: Inhambane County hotels actively contribute to the infrastructure improvement that increases the population's "well-being".

The assessed indicators were the contribution to housing improvement, sanitation, security, transport, energy, health and education.

- Hypothesis 4: The hotels in Inhambane County operate according to consistent environmental preservation policies.

The indicators to be used were the efficient energy and water management modes, the waste and residues appropriated treatment, the use of recycling or alternative energy sources, the design of construction and materials used, and the ways to inducing the guest’s environmentally responsible behavior.

Two essential target groups were identified for the study's pursuit:

a) Hotel managers:

All commercial establishments offering accommodation and food services to their customers, even if only on a bed and breakfast basis, were considered hotel units.

In this context, it was attempted to cover the entire universe under study and the 30 hotel units in the county were contacted. Of the universe in question, 22 hotel units were available to collaborate with the study, which totals 73% of the universe.

b) Hotel staff:

The criteria for determining the hotel unit workers' sample was they were Mozambican citizens and had permanent residence in the County of Inhambane before working in the hotel units under study. Thus, according to Ferreira and Campos (2009, p.26), the non-probability "Snowball" sample was used.

The total number of workers from the County of Inhambane was 428. According to the survey system parameters, the sample size for a 95% confidence level is 203 employees. A total of 216 workers were interviewed.

According to Quivy and Campenhoudt (2005, p.164), "indirect observation" through the application of questionnaires and semi-structured interviews was chosen as observation instruments.

For data treatment, the statistical analysis of the results and their graphical demonstrations were made based on two computer software: Microsoft Excel 2013 and SPSS 13.0 for Windows, while in the interviews the discourse analysis was used.

3. LITERATURE REVIEW

3.1 The hotel's contribution to the local communities socio-economic development.

According to Mrema (2015), there are so many bibliographical references that address the tourism phenomenon and its contribution to the hosts communities socioeconomic development. However, there are few reflections that focus on the specific effects of the hotel industry in the pursuit of this desired development.

Despite this reality, as the hotel industry is the main player in the tourism sector, it is easy to see that many of the aforementioned socio-economic benefits arising from tourism activity are largely catalyzed by hotel operation, because according to Ogunleye and Adesuyan (2012) the hotel industry comprises more than 60% of all tourism services.

So Cain (2012, p.1) asks: “how can a luxury hotel make a difference in the lives of average people living in the community around it? (…) This is particularly important to some of less developed countries heavily reliant on tourism”.

According to Ajake (2015), the weight of the hotel business in the tourism activity scope is justified by the range of services it covers, since a single hotel unit can provide in addition to primary and essential services such as accommodation and food, complementary services such as convenience stores, entertainment services, transport services, business and conference centers, among many others. All this diversity of services offered by hotels is very important for observing one of the main benefits attributed to tourism in the socio-economic sphere: its multiplier effect.

For Mousavi et al. (2017) and Rosa e Silva (2017), the most striking socio-economic benefits resulting from hotel operation are related to the vast capacity to contribute to local economies through the creation of jobs, tax payments, attraction of foreign currency, collaboration with local industry, local trade and promotion of the social welfare infrastructures.

Regarding to the creation of social welfare infrastructures, Ajake (2015) and Cain (2012) refer that the hotel industry has extremely important indirect socioeconomic impacts for local communities by helping them to create infrastructures to support tourists from leisure to health and basic life support. It also helps to create an adequate transport network, the emergence of tourist guides, support for artistic and craft forms and, finally, the promotion and encouragement of an appropriate public safety policy.

Despite all the socio-economic benefits mentioned above, Cain (2012) warns that the impacts may differ due to some factors such as: the local availability of construction materials, equipment and inputs against the need to import them, the local availability of skilled labour against the need for expatriates and imported manpower and the existence of taxes levied on hotel operations or on guests. Another important factor is the type of operations and hotel products practiced in the hotel units, as well as the mentality of their managers. For example, a luxury hotel that provides a wide range of services to its guests will certainly create more jobs, tax revenue and foreign exchange than a hotel whose services are aimed at less demanding guests. However, for this to happen, Masa'deh et al. (2017) and Sajjad (2018) observe that it is imperative that the hotel units always keep in mind the notion of their social responsibility that includes obligations such as respect for human rights, promotion of health and safety at work, favorable conditions for a healthy work atmosphere, preservation of culture and local identity, promotion of equal opportunities, engagement with the sustainable development of host communities, among others.

In this perspective, Cain (2012) adds that the impact that hotel units may have on the communities socio-economic development, especially in developing countries, is directly linked to the quality of the jobs they create, with the percentage of purchases they can make within the community and with the commitment they can establish with the inhabitants around them.

Mrema (2015) also highlights the importance that the hotel industry can have in supporting local development by promoting actions with agricultural producers. As barriers to the effective contribution of the hotel sector to the host communities socioeconomic development, the author highlights the weak local community financial capacity to undertake professional activities to support hotels, their scarce professional training and educational qualifications to benefit from professional opportunities that ensure, in addition to a considerable wage improvement, occupy positions with decision-making capacity and finally an inadequate link between the hotel sector and other activity branches such as agriculture or fisheries that allow the local community to easily drain their products, enhancing their endogenous resources.

For ILO (2010), the hotel sector is an employer par excellence. While it looks for mass workers, it also offers employment opportunities of the most varied professional qualifications, contributing to the employability of young people, women and immigrants and thus to their social inclusion. However, the quality of hotel employability is also characterized by being extremely heterogeneous and in some cases socio-economically unproductive. It is relatively common for the hotel industry to have low wages, part-time working hours, temporary and seasonal employment contracts. The ILO even reveals that the precariousness of the employment offer in the hotel sector can be so great that it is not uncommon to have informal labor. Another factor that characterizes the hotel labor is its youth, on average below thirty-five years of age, a factor that fits perfectly in developing countries that demographically have a very young population.

Vasquez (2014) reveals another problem regarding the hotel sector quality of employability, the workforce retention. High turnover rates are counterproductive to socio-economic stability as they represent uncertainty about job retention as well as hampering the improvement of professional qualifications, whether through training or the accumulated on-the-job experience.

The socio-economic development is not only fuelled by economic factors. This type of development is also based on pillars such as environmental sustainability, human development and equity and social justice. Mousavi et al. (2017) warns that the hotel units have strong environmental impacts on the host communities such as: water, energy and chemicals excessive consumption or high waste production. Compared to other industries, it is indisputable that the hotel industry is environmentally sensitive. Rosa and Silva (2017) even advocate that “the hotels generate environmental impacts that may contribute to global warming and the depletion of natural resources”.

In this context, for Lim (2002), Kasim and Scarlat (2007) and Grosbois (2011) operational measures should be implemented aiming at efficiency in the use of light bulbs, air conditioning, refrigerators, freezing chambers, taps, irrigation systems, swimming pools, water and waste treatment, waste recycling, maintenance of gardens and green spaces, among many others. So, according to Masa'deh (2017) and Sajjad (2018), this not only means a huge reduction in the hotels "environmental footprint", but also contributes to a marked reduction in their operating costs.

Notwithstanding the operational measures presented above, Tixier (2008) considers it the responsibility of the hotel owners to communicate and encourage the guests to also take a socially and environmentally sustainable stance in the interest of the local economy. In this way, hotels should communicate through what they are, what they say and the operational attitudes they adopt. Thus, environmental policies, appropriate practices or compromises should be in the rooms for guests to read. Awareness cards should be placed on towels and bed linen, brochures and flyers may inform guests of sustainable activities in which they can get involved. In order to ensure sustainable attitudes of their guests, hotel units can create ethical conduct codes for their guests and make this information available on their websites before tourists make their bookings.

The author also explains that the communication between hotels and guests is rarely conspicuous, except when the hotels are in nature reserves, have an eco-label or have no competition. In the overwhelming majority cases the hotels prefer to communicate almost indirectly, leaving in the air a window of opportunity at the mercy of the guest's option, an attitude that is not considered at all incorrect.

Other hotels or resorts prefer not to take any illustrative awareness measures but their actions speak by themselves: setting the example they educate their guests. The first step is to have substantive actions instead of showing that their sustainability commitments are only made of words. To happen this, Rosa and Silva (2017) emphasize the importance of hotel workers engagement by stating that “the motivation of employees also contributes to the implementation of an environmental management system”.

With regard to raising guests' awareness for social sustainability, measures can be implemented such as encouraging contributions to social support funds, donations to foundations or non-governmental organizations, creation of itineraries that foster direct contact with the local community, demonstrations of the local culture in hotels through music, dance, crafts, through recreational or sports activities sponsorship, showing endogenous cultural nature videos on the screens at public spaces, among others (TIXIER, 2008).

However, according to Mousavi et al. (2017), “sustainable practices can be considered altruistic from the perspective of guests, providing a more positive perception of particular hotels that champion such practices”. This fact constitutes a competitive advantage that can no longer be ignored.

3.2 The multinational hotel companies impacts in developing countries.

As known, most developing countries are characterized by extreme social inequalities. In addition to a large section of the population living on the poverty line, there is also a small middle class compared with the developed countries. Fueled by poverty, sometimes even by military and social conflicts, and with an extremely young population, the society of developing countries does not have the cultural habit or the financial strength to make leisure trips and then stimulate domestic tourism. In this context, the attractiveness of international tourism becomes vital for countries that want to make the tourism sector a driving force for their socio-economic development.

In this way, multinational hotel companies play an extremely important role in attracting international tourists. For Kusluvan and Karamustafa (2001, p.179) “Multinational hotel companies (…) play a key role in the development and continuity of an international tourism industry in developing countries”. After all, tourism companies from developing countries do not have the global projection, know-how, credibility or influence capable of turning their territories into points of interest on international tourism routes.

It is from this reflection that the above-mentioned authors trace the multinational hotel units impacts in developing countries: (1) bring the necessary financial investment to catapult the local tourist activity quality to international standards; (2) transfer of know-how in territories with low level of technical knowledge, (3) establish the essential contacts with the major global tour operators in order to enter these destinations in the international tourist route, (4) achieve more efficient levels of operation than local units thanks to the "professionalization" of management and the occupancy rates they achieve, (5) contribute substantially to improving the destination images by offering quality and safety services to tourists through their reputation and relationships of trust, (6) raise the quality and competitiveness bar for local hotels and (7) promote the adoption of international management techniques among local entrepreneurs.

However, the authors also detail six possible adverse effects of establishing such companies: (1) the multinational hotel units involvement can reduce the economic benefits of tourism exploitation for local communities as they are prone to hiring foreign labor to take on management and decision-making positions and are often tempted to transfer their operating profits to their origin countries, encouraging economic leakages, (2) can boost tourism demand in a given area and can opt for operational strategies that are counterproductive to the social, environmental and even economic sustainability that is required, (3) in cases of unforeseen and unfavorable events, such as terrorist attacks or escalating violence, multinational hotels are less committed to patriotic or regional causes and more flexible to decapitalize investments, creating depression in the tourist market, which is difficult to recover, (4) there may also be an over-reliance on multinational units in the pursuit of local socio-economic development, and no real endogenous driving force capable of ensuring sustainable and autonomous development based on local resources can be established, (5) this fact can generate a "foreign domination" climate, this happens when the weight of employability and tourist attraction on the part of multinational hotels is such in a certain destination that the self-determination of local authorities in matters like land use is called into question, (6) this type of hotel, many of them on an all-inclusive basis, can lead to environmental deterioration, decline in the population quality of life or a local cultural identity loss.

In this context, to capitalize these hotel companies' positive effects and mitigate the negative effects, Kusluvan and Karamustafa (2001) suggest an action plan carried out by developing countries. The first step that developing countries should take is to identify the usefulness, or not, of attracting multinational hotel companies. Whether the answer is affirmative, it should be established how the involvement will be done, whether through public-private partnerships, direct investment, management contracts, franchising. A whole set of participatory possibilities that list their specific characteristics and determine differentiated modes of development.

Then, the scale of the tourist demand to be captured must be defined. This definition, which is a factor of attractiveness for possible investors, will influence the hotel accommodation capacity to be built, the hotel services quality to be provided and even the type of tourism segment to be explored. Hereupon, a sectoral linkage plan must be drawn up. Almost as a cluster, conditions should be created so that the hotel industry exploitation multiplier effect is flourishing. Activities such as agriculture, fisheries, manufacturing, occasional trade or tourist entertainment should be organized in such a way as to satisfy as much as possible the operational needs of hotels, minimizing imports and enhancing the retention of wealth generated in the territory of destination.

It is also essential to promote the local people employability, as advocated by Masa'deh et al. (2017), Rosa e Silva (2017) and Sajjad (2018), considering the improvement of their living conditions through increased income, improved housing and health conditions, among other aspects. In countries with low educational levels, it is essential that multinational hotels not only promote employability but also invest in the professional training of their workers as well as assist local educational institutions (MASA'DEH, 2017). This practice will mean that more people in the local community in the medium term will be able to enjoy more skilled, financially profitable and decisively more dominant jobs.

On the part of the government authorities, it is necessary to implement policies to monitor and control the multinational hotel' management practices in order to ensure their effective contribution to the local communities socio-economic development. Teams should be set up to monitor investment proposals and their socio-economic effects, hotels should be subject to periodic and rigorous checks on their various aspects, publications of room prices and occupancy rates should be mandatory, should be identified operations that constitute unfair competition practices between multinational and national hotels, should be formulated legal applications that strongly condemn bribery practices and the payment of services through vouchers or credits should be limited between tour operators and hotels (KUSLUVAN & KARAMUSTAFA, 2001).

Finally, the aforementioned authors mention that well-defined criteria should be established for incentives for the multinational hotels' establishment in a given territory since these should only serve as a start-up and never as a factor that promotes unfair competition or obscure favors.

4 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

4.1 Characterization of the study area

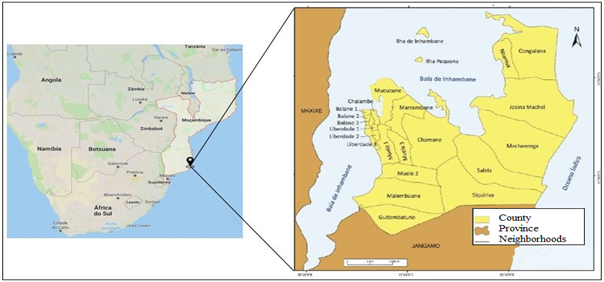

The County of Inhambane, represented by figure 1, is located in the homonymous Province and houses in itself the City of Inhambane. Established as the main leisure tourist attraction in the country, it contains two of the most famous beaches in Mozambique: Praia do Tofo and Praia da Barra. According to INE (2013), the municipality has a 195 Km2 area, with a population of 73,948 inhabitants, of which more than 37% are under 15 years old.

Figure 1: Map of Inhambane County

|

|

Source: adapted from Azevedo et al. (2017)

According to the Strategic Plan for Tourism Development in Mozambique (2016, p.13) "at the level of accommodation facilities, Inhambane province has the largest number of registered tourism enterprises" in Mozambique. In addition, worthy of note is the fact that in 2017 Inhambane province led the national ranking in terms of occupancy rates with 47.2% and the average stay of guests with 5.6 days (INE, 2018).

Another interesting fact is that if the city of Inhambane is configured as a tourist destination for leisure (sun-beach and ocean activities), this is part of the most sought after destination typology in Africa, because according to the WTO (2011) 49% of tourists on African soil in 2020 will be seeking leisure.

However, the tourist strength of Inhambane County does not translate effectively on the welfare of its population. Observing INE data (2013), in its document entitled Statistics of the District - City of Inhambane, it is concluded that the "Indicators of Welfare" of the Inhambane County are very poor. As an example of this, 73% of the population has a straw dwelling, only 42% use piped water and only 32% have electricity. Given these data, it seems evident that despite the apparent Inhambane County success as a tourist destination, the results of the exploration of this activity still reach the general population in an incipient way.

4.2 Characterization of the Hotel Units

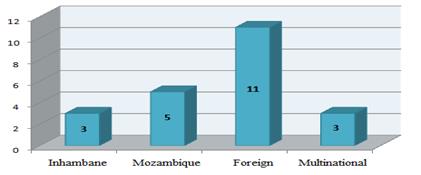

Analyzing the hotel units surveyed, it was observed that the Inhambane County tourism development is largely based on foreign and multinational tourism companies, since 64% of the hotel units based in the county, partially or totally, are the result of foreign capital investments.

Chart 1 - Number of hotel units by origin of capital invested

Source: Elaborated by the author (2017)

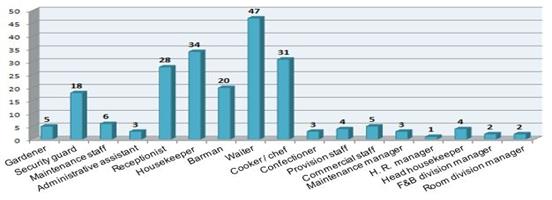

This fact leads to a visible importation of international labor force to the management positions, constituting Hjalager (2007), who states that import labor is a recurrent practice to fill the lack of know-how once that 59% of the hotel units have foreigners in managerial positions, leaving the local workers with the lower qualified positions as expressed in chart 2.

|

|

Chart

2 - Number of local workers per position held

Source: Elaborated by the author (2017)

However, the aforementioned author also argues that by internationalizing themselves, tourism companies must bet on the development of integrated clusters and services in order to become competitive. This reality in the County of Inhambane is not observed. Perhaps because they are small companies, only 23% of them claim to have a second economic activity in the county.

What is also not evident is the ideas advocated by Sharpley and Telfer (2008) when they state that international tourist establishments provide destinations with quality infrastructure and a unique capacity to attract international tourism. This is due to the fact that the Inhambane County has not yet been able to capture the investment of major international hotel brands with due recognition of quality and trust standards.

In this way, the hotel developments of the County of Inhambane consist mainly of lodges, supported by small hotels and guesthouses.

4.3 Characterization of Local Workers

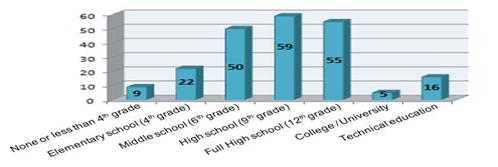

The employees of the hotel units from the local community fit in almost perfectly with ILO (2010), mostly aged between 20 and 35, occupying a wide variety of professional positions at operational and intermediate level and with heterogeneous but poorly qualified qualifications, mainly between 4th grade and 12th grade (3rd year of high school).

|

|

Chart

3 - Number of workers surveyed by education level

Source: Elaborated by the author (2017)

The "surprise" lays in the small number of female workers, estimated at only 34% of the total workforce. This reality is underpinned by strong cultural factors, factors that still subjugate Mozambican women by referring them only to domestic chores after marriage. This causes a reduction in the hotel industry contribution to the local population family budgets.

As Mozambique is a developing country, the lack of labor qualification that characterizes local workers turns out to be natural, since 61% of human capital claims that they do not have any type of vocational training for the functions they perform.

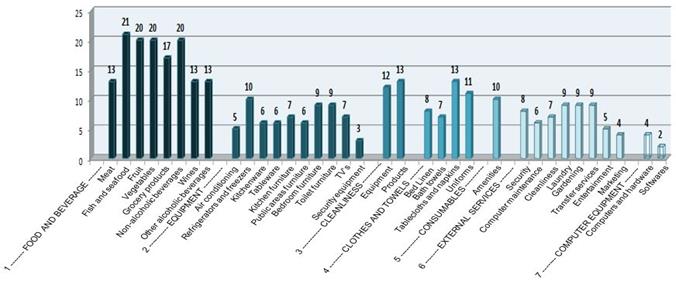

4.4 Hotel Operations' Multiplier Effect on the County of Inhambane Economy

After a detailed analysis of the services and products consumed by the Inhambane County' hotel units, a reality is undeniable: with the exception of food and cleaning products, chart 4 shows that more than half of the hotel units do not use suppliers of the Municipality of Inhambane to meet their needs.

Chart

4 - Number of hotel units that buy products and services provided by companies

based in the Inhambane County

Source: Elaborated by the author (2017)

This is explained by Mrema (2015), when the author states that sometimes the host communities in developing countries do not have the financial capacity to undertake professional activities in support of the hotel sector or do not have sufficient professional training to provide them with the required quality of services.

When confronted with the reasons for not consuming more products or services in companies based in the county, the hotel units mention two main reasons: the excessively high prices and the lack of supply.

However, the fact that Inhambane is 490 kilometers from Maputo, the capital city of the country and its main economic and commercial center, can not be ignored. This contributes to the fact that Inhambane traders incur large transport costs in the act of purchasing the goods, a cost that inflates the prices charged by local trade.

In order to combat the incipient hotel units’ multiplier effect on local trade, Kusluvan and Karamustafa (2001) recommend that a strategy of sectoral linkages be developed. Traders, farmers, fishers, artisans and others should act together, creating groups, associations or cooperatives that help to acquire cheaper products or raw materials through economies of scale, as well as finding profitable solutions to drain their products. Then, clusters should be created that allow the local hotels and traders to operate in a network of supply of products and services that safeguards the retention of tourism revenue in the Inhambane County territory.

A very different scenario is related to the space that the hotel units provide for local artists to exhibit their work. Thus, 55% of the establishments hire local artists for tourist entertainment purposes, although on a non-regular basis, and 64% help the local artistic expression marketing.

This hotel units behavior, of manifest support to local artists and even using them as a means of tourist entertainment in a time-spaced manner, reflects, according to Cunill (2009) and Yu, Byun and Lee (2014), that the hotel units in the County of Inhambane have a regiocentric cultural orientation, since they seek to give their establishment an atmosphere that reflects the socio-cultural reality where it is inserted, although they have concerns about pleasing all types of customers.

Finally, it is important to note that 41% of the hotel units have admitted that they have booking centers outside Mozambican territory. According to Nowak and Sahli (2010), the fact that the hotel units of the county have foreign or multinational character, associated with the existence of booking centers outside the country increases exponentially the economic leakages probability.

4.5 Quality of the Job Offer Provided by the Hotel Units

The job offer quality of the hotel units in the County of Inhambane cannot be dissociated from the economic context to which the county is subject. Thus, it is worth remembering that INE (2012) estimates the unemployment rate at around 25%. In addition to this economic reality, there is a hotel universe composed of small-scale enterprises, without much financial power, in which half of them do not employ more than 10 workers and only 23% of the hotel units employ between 30 and 60 workers.

On a positive note, the reduced use of informal employment is noteworthy. An data collected analysis shows that more than 91% of workers have an employment contract. Another positive highlight is the fact that the overwhelming majority of workers have permanent contracts (with no predetermined term) as well as a full-time working regime, since it provides security as to the maintenance of their jobs in the long term.

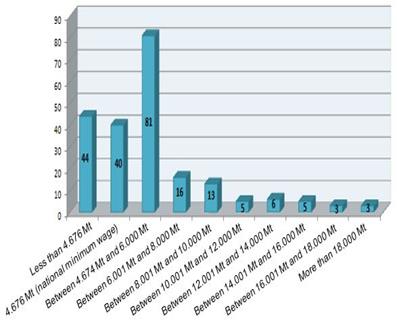

However, when the wages are observed, it is noted that the hotel unit workers are surrounded by an enormous precariousness. Incomprehensibly, 20% of workers claim to receive below the national minimum wage. This circumstance is characterized by a great disrespect of the hotel units for Mozambican labor laws, a fact that can only be observed in the light of economic neoliberalism, as Hill (2003), Harvey (2007), Reid (2003) and Zhao and Li (2006).

More seriously, this practice is difficult for the competent authorities to ascertain since the hotel units pay social security contributions on the minimum wage, which is included in the employment contracts, but which, through coercive mechanisms, the units end up not paying their workers.

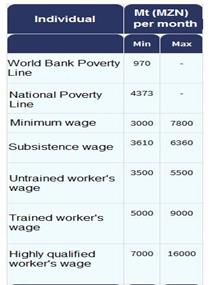

Continuing to analyze the wages earned by the hotel unit workers, chart 5, it is verified that 19% of them receive the minimum wage (4,676 meticais) and that 38% earns between the minimum wage and 6,000 meticais. Crossing these data with those of the WageInidicator Foundation (2016), table 1, it is concluded that 77% of Inhambane City hotel workers are below the national poverty line or, at most, earn living subsistence wages.

|

Chart 5 – Number of workers by wage level

|

Table 1 – Standard of living in Mozambique

Source: WageIndicator F. (2016)

|

As for the extra wages, the panorama is not very different. Many workers (38%) say they do not have any extra wages, and the most practiced are on-the-job feeding and transportation allowance. The worst scenario is related to professional training activities, whose majority of workers (73%) affirm never to have enjoyed.

Thus, Zhao and Li (2006) argue that most of the jobs occupied by local community’s members are low-wage, low-skilled and powerless.

Analysing the working time that each worker has in their hotel unit, it can be seen that 63% of the workers surveyed have no more than 4 years of work. This high percentage, according to Vasquez (2004), may indicate that the hotel units are unable to retain their labour force, incurring high turnover rates, which are obviously counterproductive to the socio-economic stability of the Conty of Inhambane.

However, despite the numbers analyzed above, workers from Inhambane County claim that they do not feel discriminated by their colleagues from other places or from foreign leaders. They show up to feel their professional performance valued by the managers, although they find their salary unfair, they evaluate their work environment as "normal".

A curious fact, and in line with what was advocated by Higgins-Desbiolles (2006), is to note that 92% of the workers are pleased with the interaction established with tourists, as they provide exchanges of experiences and foster the knowledge of new languages and cultures.

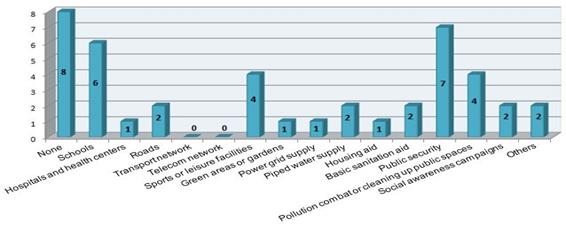

4.6 The Hotel Units Contribution to Local Welfare Infrastructures

The fact that hotel projects in the County of Inhambane are of a small size means that the hotel units do not have the economic or structural weight to contribute significantly to the construction or improvements of the local population basic infrastructures, however, they have supported several social responsibility campaigns. This is corroborated by 64% of the hotels, affirming that they have already supported social institutions.

With regard to the contribution to the infrastructure in the Inhambane County or the support to community awareness campaigns, 64% of hotel establishments also claim to have already contributed, in line with what was explained by Cain (2012) and Ajake (2015). Support for school infrastructures, sports and leisure facilities, roads, piped water networks, aid to basic sanitation, public safety campaigns, pollution control or cleaning of public space such as beaches and gardens and social awareness campaigns such as the fight against HIV / AIDS.

|

|

Chart

6 - Number of hotel units that support infrastructure or campaigns in the

Inhambane County

Source: Elaborated by the author

Despite the relative aid from the hotel units to the infrastructure of Inhambane County, there is no prospect of concerted policies by the State authorities to make this happen. Policies aimed at sponsoring social campaigns, neighborhoods, squares, gardens, sports areas, schools, hospitals and health centers or access roads should be carried out, benefiting the hotel units themselves with the display of advertising panels, naming rights or simply enjoying positive discrimination measures over municipal services.

The relationship between the hotel units and the educational institutions based in the county is also a cause for concern. A relationship that should be fruitful for both parties, but that only 14% of the hotel units assume to have established on a regular basis. Guilt should also be attributed to educational institutions, especially the Inhambane Superior School of Hospitality and Tourism, which is unable to build bridges and awaken hotel institutions to the strategic alliance's benefits.

4.7 The Hotel Units’ Environmental Preservation Policies

The Inhambane County faces serious environmental support problems, since the county only has open-air dumps and does not have sanitary landfills or a basic sanitation network. However, there are companies based in the county able to treat separated waste.

It can be said that the impact of the hotel units on the environment results from three distinct sources: construction, operational activities and decommissioning.

As the most striking construction impact, most of the hotel units are located on the first coastline, on top of the dunes or invading the space reserved for mangroves.

Regarding the operational impacts, there is a possible groundwater contamination by the hotel units septic tanks, the lack of awareness of the organic or low-industrialized food products purchases, the excessive water and energy consumption due to the lack of automatic consumption reduction systems, scarce renewable energy sources use and little practice for the separation and recycling of waste produced.

Thus, according to Lim (2002), Kasim and Scarlat (2007) and Grosbois (2011) it is urgent to implement efficient systems to reduce energy consumption such as low-consumption light bulbs, automatic taps, automatic light systems with presence detectors, automatic irrigation systems, water and waste treatment systems and, of course, the simple task of separating waste and creating conditions for its recycling.

In order to minimise operational impacts, Tixier (2008) warns that hotel units should have strategies to raise guests' awareness of the adoption of environmentally responsible behaviors. In this context, 77% of the hotel units strive to shape of their guests behavior through oral communication, information on websites, informative cards in the rooms about the use of taps, replacement of towels and bed linen and the use of air conditioning and mandatory conduct standards by guests previously communicated before the booking act. However, alternative forms could be used, such as the use of televisions in the public space to broadcast audiovisual campaigns, the use of flyers or the implementation of guest awareness campaigns using playful activities involving local flora and fauna.

The impacts of decommissioning are mostly related to the lack of sanitary landfills for the debris treatment resulting from demolitions.

5. CONCLUSION AND FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

The international character of the hotel units established in the Municipality of Inhambane cause a remarkable economic leakage to their countries of origin, through booking centers abroad. As these are of small dimensions, the positive effects linked to the improvement of the services quality or even in helping the destination international image are scarce.

The neoliberal personality of the hotel units operations in the county is too evident. This fact leads, among other aspects, to the first coastline environmental degradation, including the mangrove forest, because the units do not face any obstacle to obtain construction permits in the first meters of the coast. Their wage practices and vision of the work's world do not stimulate the improvement of social equity.

However, in a society very affected by unemployment and lack of professional qualifications, the employability generated by hotel units is extremely important. Despite the small size of most hotel units, they provide a livelihood for countless families in the local community, especially those who are furthest from the urban center of the county. On the other hand, even though little is invested in professional training, the experience acquired by workers in their daily activities is of paramount important to acquiring skills. It is also important to note that the hotel units provide the opportunity for direct contact between workers and tourists resulting in exchanges of experiences ranging from the learning of new languages to the opening of new horizons and perspectives of life.

The signs of precariousness that characterize their job offer must be eradicated as soon as possible. It is urgent to dignify the hotel workforce, it is essential to qualify and remunerate it fairly. Only in this way will hotel units be able to lower their turnover rates, increase their workers satisfaction, provide quality services and contribute even more to attracting tourist demand in the county, generating even more socio-economic benefits for Inhambane.

In turn, the hotel operations multiplier effect on the local economy is small. Since the local community does not have the financial power to undertake major commercial activities, the hotel units are deprived of making many of their goods and services purchases from companies based in the county. Thus, more financial incentives should be given to local entrepreneurship.

All these factors, especially the precarious employment situation and the lack of participation in the local economic development, hinder the existence of a local community mobilizing wave around the hotel sector installed in the county. Therefore, the following qualitative measures of hotel operations that promote a more sustainable economic development in the County of Inhambane are proposed.

a) Multiplier Effect

As strategies to improve the multiplier effect of hotel operations on the Inhambane County economy, it is suggested: 1) the investment in the county typical gastronomic offer, leading to an increase of the locally produced food consumption, 2) the use of endogenous raw materials in the future hotel units construction or in the existing ones remodeling, 3) hotel units decoration with more motifs and works art produced locally, 4) a considerable increase in the frequency in hiring local artists as a form of tourist entertainment, 5) the creation and promotion of more tourist itineraries among local communities, 6) the closure of existing booking centers outside the County of Inhambane and 7) the creation of clusters involving local traders in order to ensure lower transport costs in the goods acquisition, lowering the products prices in local commerce, diversifying supply and effectively increasing commercial transactions between hotel units and local suppliers.

b) Job Offer Quality

In order to improve the job offer quality, it is suggested: 1) a considerable increase in the professional training of workers investment, 2) a financial effort to practice wages above 6,360 meticais, wages considered as subsistence, 3) an increase in extra-wage benefits, mainly in food subsidy terms, 4) an increase in the wage revision frequency, as inflation in Mozambique is accelerated, 5) foster an increase in people from the local community in intermediate management posts and 6) invest in policies to mitigate turnover, thus contributing to job stability.

c) Contribution to 'Welfare' Infrastructure

As policies leading to an increase in the hotel units contribution to the "well-being" infrastructure improvement, it is suggested: 1) increased support or sponsorship to social institutions, 2) increased pressure on local authorities for the extension of the electricity and water supply network to the areas where their hotel units are implemented, 3) increased financial aid to hospitals and health centers, 4) expansion of their commercial activity for the transport sector and 5) exponential increase in protocols with educational institutions in Inhambane County, especially with those focused on hospitality and tourism.

d) Environmental Preservation

Regarding the environmental preservation measures that can be implemented by the hotel units, it is suggested: 1) an increase in the organic or slightly industrialized food products purchase, 2) the acquisition of automatic systems to reduce water and energy consumption, 3) an increase in the renewable energy sources usage, 4) an exponential increase in waste separation and recycling, 5) the acquisition of water treatment and reuse systems and 6) the hotel units with a privileged location near the coast should strengthen the cooperation with maritime authorities, mainly regarding the illegal shark fishing.

6. REFERENCES

AJAKE, A. O. Assessing the Impacts of Hospitality Industry in Enugo, Nigeria. American Journal of Tourism Managemet, Rosemead (CA), v.4, n.3, p. 43-53, 2015.

AZEVEDO, H; NHANTUMBO, S. & BANZE, E. Políticas Públicas e Desenvolvimento Turístico em Moçambique: Análise da Implementação do Plano Estratégico do Município de Inhambane (2009-2019). Geo UERJ, Rio de Janeiro, n.30, p. 253-270, 2017.

CAIN, C. L. Assessing the Economic Impact of Hotel Investments. San Diego: Global Hospitality Resources, 2012.

CUNILL, O. M. The Growth Strategies of Hotel Chains: best business practices by leading companies. New York: Routledge, 2009.

CZAIKA, M. & NEUMAYER, E. Visa Restrictions and a Economic Globalisation. Applied Geography, Oxford,v.84, p.75-82. 2017.

DE PIERI, V., & PANOSSO NETTO, A. Turismo internacional: fluxos, destinos e integração regional. Boa Vista: UFRR, 2015.

FERREIRA, M. J. & CAMPOS, P. O Inquérito Estatístico – uma introdução à elaboração dos questionários, amostragem, organização e apresentação dos resultados. Lisboa: ALEA, 2009.

GOVERNMENT OF INHAMBANE PROVINCE. Plano Estratégico da Província de Inhambane (2011-2020). Inhambane, 2010.

GROSBOIS, D. Corporate social responsibility reporting by the global hotel industry: Commitment, initiatives and performance. International Journal of Hospitality Management, Oxford, v.31, n.3, p. 896-905, 2011.

HARVEY, David. Neoliberalismo como Destruição Criativa. Revista de Gestão Integrada em Saúde do Trabalho e Meio Ambiente, São Paulo, v.2, n.4, p. 1-30, 2007.

HIGGINS-DESBIOLLES, F. More Than an “Industry”: the forgotten power of tourism as a social force. Tourism Management, Oxford, v. 27, n.1, p. 1192-1208, 2006.

HILL, Dave. O Neoliberalismo Global, a Resistência e a Deformação da Educação. Currículo sem Fronteiras, v.3, n.2, p. 24-59, 2003.

HJALAGER, Anne-Mette. Stages in The Economic Globalization of Tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, Great Britain, v.34, n.2, p. 437-457, 2007.

HRUBCOVA, G.; LOSTER, T. & OBERGRUBER, P. The Economic Effects of Tourism in the Group of the Least Developed Countries. Procedia Economics Finance, London, v.39, p. 479-481, 2016.

INSTITUTO NACIONAL DE ESTATÍSTICA. Anuário Estatístico 2017. Maputo, 2018.

INSTITUTO NACIONAL DE ESTATÍSTICA. Estatísticas do Distrito – Cidade de Inhambane. Maputo, 2013.

INSTITUTO NACIONAL DE ESTATÍSTICA. Inquéritos Contínuos aos Agregados Familiares. Maputo, 2012.

INTERNATIONAL LABOUR ORGANIZATION. Developments and Challenges in the Hospitality and Tourism Sector. Geneva: ILO, 2010.

JAFARI, J. Preparing for Tomorrow... Glocalization of Tourism, which image to project?. In XV Seminário ANPTUR. São Paulo. 2018.

JAVID, E. & KATIRCIOGLU, S. The Globalization Indicators-Tourism Development Nexus: a dynamic panel-data analysis. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, London, v.22, n.11, p.1-13, 2017.

KASIM, A. & SCARLAT C. Business Environmental Responsibility in The Hospitality Industry. Management, Koper, v.2, n.1, p. 5-23, 2007.

KRIPPENDORF, J. Sociologia do Turismo: para uma nova compreensão do lazer e das viagens. São Paulo: Aleph, 2003.

KUSLUVAN, S. & KARAMUSTAFA K. Multinational Hotel Development in Develiping Countries: an exploratory analysis of critical policy issues. International Journal of Tourism Research, New Jersey, v.3, n. 3, p. 179-197, 2001.

LIM, C. The Socioeconomic Importance of Eco-Resort Management Practices. In: 1ST BIENNIAL MEETING OF THE INTERNATIONAL ENVIRONMENTAL MODELLING AND SOFTWARE SOCIETY. Proceedings, Lugano: iEMSs, 2002.

LIU, X. & LI, J. Host Perceptions of Tourism Impact and Stage of Destination Development in a Developing Country. Sustainability, Basel, v. 10, p. 2-15, 2018.

MASA’DEH, R.; NASSEEF, M.; SUNNA, C.; SULIMAN, M. & ALBAWAB, M. The Effect of Hotel Development on Sustainable Tourism Development. International Journal of Business Administration, Toronto, v.8, n.4, p.16-33, 2017.

MINISTÉRIO DO TURISMO. Plano Estratégico para o Desenvolvimento do Turismo em Moçambique 2016-2025. Maputo, 2016.

MOUSAVI, S.; HOŞKARA, E. & WOOSNAM, K. Developing a Model for Sustainable Hotels Northern in Cyprus. Sustainability, Basel, v.9, p. 1-23, 2017.

MREMA, A. A. Contribution of Tourist Hotels in Socio-Economic Development of Local Communities in Monduli District, Northern Tanzania. Journal of Hospitality and Management Tourism, Nairobi, v.6, n.6, p. 71-79, 2015.

NOWAK, Jean-Jacques & SAHIL, Mondher. Should Tourism Be Promoted in Developing Countries? Private Sector & Development, September, v.7, p.11-13, 2010.

OGUNLEYE, O. S. & ADESUYAN A. J. Tourism and Hospitality, Issues and Strategies for Sustainable Socio-Economic Development in Ondo State, Nigeria. In: 2ND ADVANCES IN HOSPITALITY AND TOURISM MARKETING AND MANAGEMENT CONFERENCE. Proceedings, Corfu Island: Research Institute for Tourism of the Hellenic Chamberof Hoteliers, 2012.

QUIVY, R. & CAMPENHOUDT, L. Manual de Investigação em Ciências Sociais. Lisboa: Gradiva, 2005.

REID, Donald G. Tourism, Globalization and Development – responsible tourism planning. London: Pluto Press, 2003.

RIVERA, M. The Synergies Between Human Development, Economic Growth, and Tourism Within a Developing Country: an empirical model for Ecuador. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, London, v.6, p. 221-232, 2017.

ROSA, F. & SILVA, L. Environmental Sustainability in Hotels, Theoretical and Methodological Contribution. Revista Brasileira de Pesquisa em Turismo, São Paulo, v. 11, n. 1, p. 39-60, 2017.

SAJJAD, A. Sustainability in the Pakistani Hotel Industry: An Empirical Study. Corporate Governance: The International Journal of Business in Society, Bingley, v. 18, n.4, p. 714-727, 2018

SHARPLEY, R. & TELFER, D. Tourism and Development in the Developing World. Oxon: Routledge, 2008.

SONG, H.; Li, G. & Cao, Z. Tourism and Economic Globalization: an emerging research agenda. Journal of Travel Research, New York, v. 57, n.8, p.1-13, 2018.

TIXIER, M. The Hospitality Business Communication and Encouragement of Guests' Responsible Behaviour and Their Diverse Responses. In: VI ESADE INTERNATIONAL DOCTORAL TOURISM AND LEISURE COLLOQUIUM - APUESTAS PUBLICO-PRIVADAS ARA LA GESTION DEL TURISMO. Proceedings, Barcelone, 2008.

UNITED NATIONS ENVIRONMENT PROGRAMME. Tourism Industry as a partner for sustainable development. United Kingdom: WTTC, IHRA, IFTO & ICCL, 2002.

VASQUEZ, D. Employee Retention for Economic Stabilization: a qualitative phenomenological study in the hospitality sector. International Journal of Management, Economics and Social Science, San Diego, v.3, n. 1, p. 1-17, 2014.

WAGEINDICATOR FOUNDATION. Nível de vida e os salários no contexto de Moçambique. Recuperado em 03 de Março, 2016, de http://www.meusalario.org/mocambique/main

WORLD TOURISM ORGANIZATION. Sustainable Tourism for Development. Madrid: UNWTO, 2013.

WORLD TOURISM ORGANIZATION. Tourism Towards 2030 – Global Overview. Madrid: UNWTO, 2011.

WORLD TRAVEL & TOURISM COUNCIL. Travel & Tourism League Table Summary 2018. London: WTTC, 2018.

YU, Y.; BYUN, W-H. & LEE, T. J. Critical Issues of Globalization in the International Hotel Industry. Current Issues in Tourism, Oxford, v.17, n. 2, p. 114-118, 2014.

ZHAO, Weibing & LI, Xingqun Globalization of Tourism and Third World Tourism Development – a political economy perspective. Chinese Geographical Science, Hong Kong, v. 16, n. 3, p. 2003-2019, 2006.

![]() This

work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International

License.

This

work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International

License.