1 INTRODUCTION

Over the last decade, customers’ views regarding consumption have transformed into a more resource-saving and efficient consumption culture (Leismann et al., 2013; Han, 2021). “Access over Ownership” strategies leading to product sharing can maximise resource utilisation and conservation while lowering risk and fixed costs (Stevenson, 1983). Koopman, Mitchell and Thierer (2015) defined the “sharing economy” as “any marketplace that leverages the Internet to connect distributed networks of persons in order to share or exchange otherwise underutilised assets”. The sharing economy has thus become a global phenomenon, which alters conventional patterns of consumption of services (Lee et al., 2020).

Airbnb is a digital marketplace where users can rent out their unused residential space to other people for a short period of time. Airbnb, a home-sharing platform, is widely considered a fantastic sharing economy success story (von der Heidt et al., 2020). Furthermore, it was considered as the poster child of the broader platform economy, an informal tourist accommodation sector with an extremely disruptive potential (Dann et al., 2019). It allows individuals to host guests without making a significant investment or bearing considerable overhead costs (Guttentag, 2015). In addition, Airbnb allows connecting people with homes, studios or rooms to rent to guests looking for a place to stay much more accessible and attractive compared with other competing home-sharing concepts. (Guttentag, 2015).

Instead of solely economic or commercial endeavours, the tourism systems result principally from policy and administrative actions. (Airey & Chong, 2011). This contradiction is highlighted by the rise of sharing accommodation platforms like Airbnb and calls for a regulatory framework that looks beyond economic stimuli (Grimmer et al., 2019). Sharing or peer-to-peer platforms have a reputation for being economic disruptors, and their nature extends beyond economics, causing policy development and interpretation to be disrupted. (Biber et al., 2017; Ranchordás, 2015). Airbnb’s phenomenal growth and popularity have made it difficult for legislators to understand the impact on their communities (Grimmer et al., 2019). While local governments and state governments recognise tourism’s economic impact (Grimmer et al., 2018), Airbnb and other comparable platforms are being increasingly targeted for regulation. Policymakers are thus encouraged to strike a compromise between regulatory frameworks to safeguard local communities and those that are intended to capitalise on the value offered by the sharing economy platforms. This is especially significant in rural and remote places (Grimmer et al., 2019).

Over the last decade, much research has been done on peer-to-peer accommodation (Dolnicar, 2019). As the short-term rental industry has risen, so has regulators’ interest, resulting in many legislative skirmishes over attempts to limit that development (Moylan, 2016). A fascinating topic for scholars and the most difficult for policymakers is how to regulate this peer-to-peer accommodation to minimise negative consequences while maintaining economic benefits (Dolnicar, 2019). Many cities worldwide are actively exploring measures to regulate Airbnb to balance the potential benefits of the platform with citizens’ concerns (Guttentag, 2015). So far, most legislation has viewed Airbnb as a typical industry participant, failing to consider many unique characteristics and failing to achieve the goal (Espinosa, 2016). Difficulties are mainly in enforcement (Edelman & Geradin, 2015a; Espinosa, 2016; Gottlieb, 2013) due to unique situations in the cities. While some communities enthusiastically welcome Airbnb’s benefits, others are continually at war with it (Oskam & Boswijk, 2016). While there is an urgent need for proper legislation and research on this topic, little has been done in academia regarding policy solutions to Airbnb (Arias Sans & Quaglieri Domínguez, 2016; Duuren et al., 2017; Gottlieb, 2013; Miller, 2014).

According to the Tourism Act, No. 38 of 2005, it is mandatory to register all institutions that engage in Tourist accommodation under SLTDA (Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, 2016). Besides the registered tourist accommodations, a surge in informal tourist accommodations can be seen due to the online booking platforms (Daily Mirror, 2015; Ellepola, 2017). It has been found that around 50% of tourists who are visiting Sri Lanka choose informal tourist accommodations over traditional tourist accommodations (Miththapala & Tam, 2017). Due to online booking platforms like Airbnb, Vrbo, Booking.com and other Online Travel Agents (OTAs), these establishments have gained massive popularity as they use the above giant booking platforms for marketing their establishments (Ellepola, 2017). The emergence of platforms like Airbnb and other such enterprises is a relatively new phenomenon. There is very little or no legislation in cities regulating these novel types of enterprises. However, residents in various regions have pressured local governments to enact laws, but little is known about how cities deal with businesses like Airbnb (Nieuwland & Van Melik, 2020). Thus, this study focuses on Airbnb’s regulatory processes by comparing short-term rental legislation from six cities and ten countries in the Asia Pacific region using qualitative content analysis to to evaluate the adequacy of existing guidelines and policies in regulating peer-to-peer tourist accommodations driven by Airbnb in Sri Lanka.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. Section two includes a literature review that provides background on short-term rentals’ positive and negative impacts on various tourism and hospitality industry stakeholders. Additionally, the review provides an account of existing regulatory attempts made by the countries and the importance of regulating rising short-term rental platforms. Next, section three presents the methodology employed to conduct this study, and section four reports the study’s empirical findings. Finally, section five provides the conclusion, including theoretical and practical implications and closes with the study’s limitations and further research avenues.

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

2.1 Impacts of Short-Term Rentals (STRs)

The literature on the sharing economy has provided numerous avenues for understanding its economic (Burtch et al., 2018; Zervas et al., 2017) and social (B. Edelman et al., 2017; Koopman et al., 2015b; Molly & Arun, 2017; Rauch & Schleicher, 2015; Sundararajan, 2014) implications. From a positive standpoint, the sharing economy has the potential to provide both the supply and demand sides with significant, rewarding benefits. In the housing setting, for example, sharing ownership can relieve some of the obligations of ownership from the hosts by letting out a portion of their living quarters to temporary visitors (Jefferson-Jones, 2015). According to Burtch, Carnahan and Greenwood (2018), the advent of the sharing economy platforms would give unemployed or underemployed people the option of launching their businesses. Meanwhile, sharing economy websites typically provide lower prices than market alternatives. Home-sharing platforms, such as Airbnb, compete directly with low-cost hotels (Zervas et al., 2017), whilst car-sharing services offer lower hiring rates than licenced taxi services (Cramer & Krueger, 2016). Sharing consumes fewer resources than consumption because it does not necessitate the purchase of new items or facilities. The sharing economy can aid in the optimal utilisation of resources such as unoccupied residential properties (Schor, 2016). The urge to socially connect with others might also encourage people to share. By staying together, residents and tourists can promote cultural interactions.

Travellers have long had access to vacation houses and villa rentals, but web marketing has allowed them to considerably expand their reach and capture a broader customer base (Van Holm, 2020). Vacation Rentals by Owners (VRBO) began operations in 1995, allowing homeowners to market their own houses, but the business exploded with the launch of Airbnb in 2008 and its subsequent growth. Airbnb, the world’s largest short-term rental website, currently operates in over 81,000 cities in 220 countries, with a revenue of more than $3.3 billion and is valued at $18 billion (Airbnb, 2021; Curry, 2021). As a result, Airbnb has altered the short-term rental industry from a niche accommodation alternative to a mainstream choice for millions of travellers.

Airbnb’s growth has been fueled in part by the competitive advantages it has over traditional tourist accommodations. Booking a room on Airbnb is typically less expensive than booking a hotel room, especially when considering the additional facilities offered in an entire property (Guttentag, 2015; Wang & Nicolau, 2017). Nevertheless, economic considerations are not the only reason people use Airbnb. Airbnb offers one-of-a-kind accommodations and wider diversity, both in terms of location and aesthetics (Amaro et al., 2018). Furthermore, tenting with Airbnb allows guests to interact with their hosts and have a more authentic experience while travelling and enjoying everyday life (Brochado et al., 2017; D. A. Guttentag & Smith, 2017; Maitland, 2010). In some ways, many such stays have little interaction with the host and resemble staying in a hotel, especially in entire place rentals. Along with the advantages for guests, offering a room or a whole residence on Airbnb has advantages for owners with increased visibility and the ability to maximize their revenue (Van Holm, 2020).

However, these benefits are immediately factored into home prices, raising the cost of buying or renting a home for the long term (Van Holm, 2020). Landlords, in particular, who have decided that it is more profitable to utilise the property as a short-term rental rather than seeking a long-term lease from tenants raise prices and drive out individuals wishing to use it as a residency. These developments increase commercial investors who buy many properties intending to just rent them out as short-term rentals (Gurran & Phibbs, 2017). There is an ongoing dialogue about whether short term rentals take away homes that would otherwise be rented on the open market, thereby transforming it from residential to commercial usage and intensifying the already-existing scarcity of rental housing. Tourism in general, and short-term rentals like Airbnb in particular, are considered to contribute to gentrification (Füller & Michel, 2014; Gant, 2015), a process that might potentially undermine a neighbourhood’s overall character as a residential neighbourhood populated mainly by permanent inhabitants (Gotham, 2005). At the scale of a building where individual apartments or rooms are rented to guests, residents may feel less secure as constantly changing guests are permitted access to shared facilities, in addition to noise and other disruptions. This is becoming more common with short-term rentals as commercial investors take up residential houses and convert them into permanent and often illegal Airbnb rentals (Gurran & Phibbs, 2017). As homes are removed from the market and rented to visitors, housing availability and affordability for local inhabitants become a concern (Jefferson-Jones, 2015; Lines, 2016). In New York, for instance, increasing the number of Airbnb locations resulted in a 6 -11 per cent increase in property values (Sheppard & Udell, 2016). Although growing property values benefit homeowners, they impact residents who can no longer afford to pay rent and are forced to leave the neighbourhood. Exclusionary displacement may occur in addition to direct displacement when housing and rental costs have risen to the point that the neighbourhood is expensive to newcomers (Gant, 2015). At the same time, Holm (2016) portrayed Airbnb as a method for people to make ends meet by producing extra revenue to pay for rising rents; unfortunately, this creates a vicious cycle in which renting out is required to pay for rising costs, which further raises rents and forces more renting out.

Short-term rentals have several adverse effects on inhabitants’ quality of life in neighbourhoods (Wegmann & Jiao, 2017). When geographically concentrated over a certain threshold, short-term rentals might create intense demand for on-street parking, obnoxious and noisy conduct by out-of-town guests at unusual hours, and other disruptions (Wegmann & Jiao, 2017). Local communities worldwide have begun to worry about the adverse effects of Airbnb accommodations in their neighbourhoods. Nuisance complaints range from visitor-caused noise to traffic, parking and waste management issues, and safety concerns when strangers enter the neighbourhood and buildings (Gallagher, 2017; Gurran & Phibbs, 2017). Residents in Barcelona expressed a loss of local culture and coherence in their neighbourhood (Gant, 2015), a concern expressed in many cities worldwide. Unlike negative housing market impacts, this quality of life impact can be imposed by any form of short-term rental, whether it is an entire place rental or otherwise, and whether a given property is rented regularly or irregularly.

2.2 Regulation of Short-Term Rentals (STRs)

As mentioned above, Airbnb has a wide range of effects on individual cities. Whether it is favourable or unfavourable depends on various factors, including the size of the city, the current tourism economy and value, location, and the intensity of Airbnb properties (Oskam & Boswijk, 2016). Nonetheless, most communities feel compelled to regulate Airbnb and other STR platforms to balance tourists’ interests and residents or businesses.

On the other hand, Regulating Airbnb seems to be a tricky and challenging business. For example, when London’s short-term rental regulations were relaxed, planners were confronted with significant informational gaps and a nearly unenforceable policy (Holman et al., 2018). The majority of efforts have relied on conventional B2B (business to business) or B2C (business to consumer) methods (Espinosa, 2016). However, because Airbnb is a peer to peer platform, it exceeds these traditional regulatory methods (Guttentag, 2015). Regulations should focus on the producers or hosts and be held accountable rather than Airbnb (Lines, 2016). However, it is difficult to determine whether hosts abide by the guidelines (B. G. Edelman & Geradin, 2015b; Espinosa, 2016; Gottlieb, 2013). Furthermore, existing policies lack the potential to minimise negative externalities, such as spatially clustering Airbnb rentals (Gurran & Phibbs, 2017).

As a result, it is challenging to introduce some sort of control over the issues without jeopardising the benefits of short term rentals. Finck and Ranchordas (2016) describe approaches that cities have adopted to cope with the sharing economy in their insightful report on the regulation of the sharing economy. They define an accommodating or minimalist approach when cities understand the value of fostering platforms and, as a result, either do not enforce their zoning restrictions or impose minimum regulations in the form of tax collection, night limits, and residency requirements. Regulations are aimed to prevent commercial interests from misusing short term rentals in the city, and it is not always successful. London is a case in point, as central government rules did little to reduce multi-listings, a standard indicator of professional operators in the market (Holman et al., 2018). Another type of involvement mentioned by Finck and Ranchordas (2016) is what they call the restrictive approach, in which cities aim to eradicate or severely limit illicit activity. Barcelona, for example, has enacted legislation and entered into a data-sharing deal with Airbnb. As a result, property owners who do not have a licence can now be traced and penalised. This is one of the first times a city has entered into a data-sharing agreement with the platform (O’Sullivan, 2018). While this is a considerable improvement over Airbnb’s more inflexible stance on data sharing, it only goes a small way toward curbing the operations of other home-sharing services. Cities are thus left to fight and negotiate with an increasing number of platforms on an individual scale.

Based on the previous studies, the author could identify three basic approaches to regulating Airbnb. They are “outright prohibition”, “laissez-faire approach”, and “limiting Airbnb with some constraints” (Guttentag, 2015; Jefferson-Jones, 2015; Miller, 2014). Laissez-faire can hardly be considered regulation because no actual measures are taken. However, in some circumstances, local governments have reached an agreement with Airbnb to collect taxes on transactions done on the platform (Lines, 2016). Prohibition entails prohibiting short-term rentals entirely, either in the entire town or in a specific district. Although this might potentially offset negative externalities, local governments would lose tax revenue and risk creating an underground market for short-term rentals (Jefferson-Jones, 2015).

Furthermore, Airbnb’s regulations are the most prevalent, with four sorts of restrictions (Nieuwland & van Melik, 2020). First, quantitative constraints include limiting the number of short-term rental accommodations available (Jefferson-Jones, 2015), the number of permitted visitors or days rented (Gottlieb, 2013; Guttentag, 2015; Miller, 2014), and the number of times an Airbnb can be rented out per year (Jefferson-Jones, 2015). Second, locational restrictions make sure short-term rentals are restricted to certain places (Gurran & Phibbs, 2017). Third, the density limitations limit the number of short-term rentals in specific neighbourhoods (Jefferson-Jones, 2015). Finally, qualitative constraints dictate the type of lodging, such as an entire apartment vs a room or commercial-style Airbnb (Jefferson-Jones, 2015). Specific safety regulations also fall under this category, such as installing a smoke detector. These restrictions are frequently combined with the requirement for hosts to get permission or a licence before renting out portions of their home (Guttentag, 2015; Miller, 2014).

Several scholars have underlined that not all cities should apply the same regulatory strategy to govern Airbnb because the effects vary depending on geographic location, the type of property rented out, and the attraction of the destination (B. G. Edelman & Geradin, 2015b; Gurran & Phibbs, 2017; Guttentag, 2015; Oskam & Boswijk, 2016). Some communities want to embrace Airbnb to boost tourism, while others want to ban it outright or test it with regulations based on taxes or safety issues (Oskam & Boswijk, 2016).

Studies have highlighted the importance of introducing short-term rental legislation (Koopman et al., 2015b; Molly & Arun, 2017; Thierer et al., 2015). City governments can use regulations to safeguard customers and existing markets (Rauch & Schleicher, 2015). Koopman, M. Mitchell and Thierer (2015) stated that short-term rental laws should evolve to meet industry realities if legislators want to safeguard customers. It is also stated that taxes are universally used in the traditional hospitality industry, such as hotels, and should be incorporated into short-term rental laws (Kaplan & Nadler, 2015). On the other hand, short-term rental regulation may raise serious legal, political, and ethical concerns. Legislators must evaluate whether sharing economy practices are worth protecting, identify the aims for regulating the short-term rental market, and consider if regulations can conform to the evolving industry while it is being implemented (Ranchordás, 2015). Although a few conceptual-theoretical and normative studies examine the role of government involvement as a viable way to regulate the short-term rental business, a complete empirical review of short-term rental regulation is lacking.

3 MATERIAL AND METHODS

3.1 Data Collection

In order to evaluate the adequacy of existing guidelines and policies in regulating peer-to-peer tourist accommodations driven by Airbnb in Sri Lanka, it is essential to understand how different cities are coming up with regulations to deal with the differential impacts of Airbnb. Therefore, the researcher has looked at policy documents from six cities and ten countries in the Asia Pacific region.

Airbnb Platform maintains a particular web page called “Responsible Hosting” under Airbnb Help Centre to provide potential and existing hosts to become familiar with hosting responsibilities and provide a general overview of different laws, regulations, and best practices that may affect hosts in different cities, countries, and regions. Hosts are also encouraged to follow Airbnb guidelines, such as Hosting Standards. The web page also provides explicit information on laws and other rules applicable to specific circumstances and locales. In addition, the web page gives information on existing laws and regulations passed and practised by various regions to regulate Short Term Rentals worldwide, namely in Asia-Pacific, Europe, and North and South America. As this study focus on the Asia-Pacific region, the researcher collected the available information about all six cities and ten countries in the Asia Pacific region from the web page. The cities and countries are mentioned in Table 01.

Table 01. Cities and countries selected for the content analysis.

|

Region |

Country |

City |

|

Asia-Pacific |

Australia |

New South Wales |

|

Tasmania |

||

|

China |

- |

|

|

French Polynesia |

- |

|

|

Hong Kong (SAR) |

- |

|

|

India |

Goa |

|

|

Gurgaon |

||

|

Karnataka |

||

|

Japan |

- |

|

|

New Zealand |

- |

|

|

Singapore |

- |

|

|

South Korea |

- |

|

|

Thailand |

- |

|

|

United Arab Emirates |

Dubai |

Source: Compiled by the Authors, 2021.

In order to facilitate comparison, relevant documents on prevailing laws, regulations, and guidelines in Sri Lanka were obtained from the Sri Lanka Tourism Development Authority (SLTDA).

3.2 Data Analysis

Qualitative content analysis is used to identify patterns, themes, and meanings in exploratory or descriptive studies (Berg & Lune, 2012) and is therefore well fit with this particular objective.

Also, it leaves room for different perspectives and the identification of patterns (Krippendorff, 2018). It is often used as a summarising approach where the aim is to seek generalisable conclusions instead of describing all details (Bryman and Burgess, 1999). Leximancer was used to analyse the collected documents. Leximancer is a software application that uses machine learning to perform quantitative content analysis. Leximancer is used to mine vast volumes of qualitative textual materials and extract information to graphically present the results in a graphic organiser of the contents known as a Concept Map. Through conceptual (thematic) and relational (semantic) analysis, the researcher can mine the data deeply to reveal the meaning hidden in its digital structures. The data analysis using Leximancer involved five key stages:

1. Formatting documents: As directed in the user manual, each document was converted to a uniform format in Microsoft Word to ensure compliance with the software.

2. Classification of documents for analysis: Each legal document was named based on the enforcement location.

3. Automatic text processing and concept seed generation: Tags were automatically assigned to identify each legal document at the file level.

4. Concept editing: The user did not define tags or concepts, and only automatically defined tags and concepts were used. Thesaurus settings were set to software default, and plurals of concepts or identical meanings were merged.

5. Concept coding: The text was coded with the file tags and “all concepts” that were identified automatically.

6. Output: To emphasise the conceptual context in which the words appear and enhance the uncovering of indirect relationships, the social network (Gaussian) map was selected over the topic network (linear) map.

The step-by-step analysis process in Leximancer is further elaborated in Table 2. The command adopted by the researcher is highlighted in bold.

Table 02. Step-by-step process of analysis in Leximancer

|

Step |

Process Options (Command entered is in Bold) |

|

1. Select documents |

|

|

2. Text processing settings |

|

|

3. Concept seeds setting |

|

|

Generate concept seeds |

|

|

4. Edit concept seeds |

|

|

5. Thesaurus settings (concept learning) |

|

|

Generate thesaurus |

|

|

6. Compound concepts |

|

|

7. Concept coding |

|

|

8. Project output settings |

|

|

Generate concept map |

|

Source: Compiled by the Author, 2021.

4 RESULTS

4.1 Text-mining results

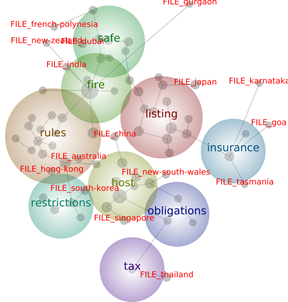

As per the analysis, nine significant themes (Figure 1) emerged from the content analysis of the documents, namely, “listing”, “rules”, “host”, “guests”, “safe”, “restrictions”, “required”, “obligations”, and “tax” based on the connectivity score (Table 3). The degree to which the topic is connected to the other concepts on the map is reflected in the connection score. It is equivalent to the degree score in network analysis.

Figure 1. Concept map of the themes and concepts

Source: Compiled by the Author (Leximancer Analysis Output), 2021.

Figure 2. Concept map of the themes (File Tagged)

Source: Compiled by the Author (Leximancer Analysis Output), 2021.

The number of hits indicated in Table 3 provides the number of text blocks related to the respective theme in the project. The concept map in Figure 2 includes the document file tags, and the concepts are clustered around the tags according to their relationship with each other. Concepts derived from a document’s content will tend to cluster near the document’s file tag in the map space.

Table 3. Analyst Synopsis of each theme

|

Theme |

Hits |

Connectivity Score |

Concepts |

|

360 |

4405 |

listing, information, Airbnb, use, number, provide, need, details, stay, contact, take, emergency |

|

|

rules |

267 |

4236 |

rules, sure, allow, neighbours, building, pets, plan, available, share, cleaning, parties, ensure, consider, noise |

|

host |

344 |

3922 |

host, regulations, property, local, including, laws, apply, additional |

|

guests |

272 |

2144 |

guests, safety, notify, guidelines |

|

safe |

167 |

2056 |

safe, clearly, home, areas, Ensure, potential, control |

|

restrictions |

106 |

1140 |

restrictions, community, check, Check |

|

required |

111 |

607 |

required, insurance |

|

obligations |

82 |

545 |

obligations, accommodation, private |

|

tax |

43 |

182 |

tax |

Source: Compiled by the Author (Leximancer Analysis Output), 2021.

4.1.1 Listing

Provisions for code of conduct, emergency contact details and medical supplies

In order to ensure the safety and peace of mind of guests, the host should make available (by means of flyers, notices, digital bulletin boards, etc.) a code of conduct and emergency instructions while outlining any potential hazards.

Code of Conduct generally refers to obligations that hosts, guests, property managers, booking platforms, and letting agents are required to meet. Emergency instructions should include,

- Local emergency contact numbers (E.g., Police Station, Fire Service Department)

- The contact number of the nearest hospital

- The contact number of the host

- A backup contact number (in case the host is unavailable or not reachable).

A host should have a first aid kit, and the location must be informed to guests while checking in. The host must ensure to check it regularly and restock if they run out.

Listing registration

Most countries require short term rentals to be registered and obtain a license or a permit under the respective authority before commencing operation. Countries like India and Japan further strengthen the requirement by mandating hosts to add the registration number to their Airbnb listing page. The Airbnb platform will remove property listings without the registration number.

Privacy

The hosts must always protect the privacy of guests. Guests’ personal information should not be disclosed to third parties unless there is a compelling reason to do so. It was also highlighted that security cameras or other monitoring technology might only be installed and used in the property’s public spaces, not in the rooms where the guests will be staying (non-public areas) and should be notified to guests.

Collecting and reporting hosting information

Several countries have entered into an agreement with the Airbnb Platform to obtain data on hosts to review the hosts’ adherence to rules and regulations. For instance, Japan has entered an agreement with Airbnb where Airbnb is required to provide listing and booking information every six months to the Japan Tourism Agency (JTA). Similarly, in China, Airbnb requires disclosing information about listings to government agencies without further notice to hosts.

Covid 19

Due to the pandemic situation, several countries have enforced special cleaning and disinfection guidelines for the property to ensure guests’ and hosts’ safety. For instance, in Japan, the authorities have introduced guidelines and hygienic standards set forth under respective laws and regulations. In addition, countries have also launched special programmes to encourage and increase awareness of the importance of such measures. For example, In China, Airbnb has launched a programme called “Rest-assured Stay”, where they add a unique tag for the listings that have met the requirements to show their commitment.

4.1.2 Host

Awareness of local laws and regulations

Countries also recommend that hosts be aware of the necessary local laws, regulations and taxes related to short-term renting apart from national laws. For instance, in South Korea, apart from related national laws and regulations, hosts are advised to be mindful of region-specific municipal government requirements.

4.1.3 Fire

Fire Safety

Countries have been mandated to include fire prevention and notification measures if the host needs to rent out their properties for guests. For example, the host must equip the property with fire safety equipment in Dubai, including fire extinguishers, blankets, gloves, and a torch with batteries. The host must also have to clearly mark the fire escape route and post a map on the property. Additionally, the host needs to equip the property with functioning automatic smoke alarms and carbon monoxide detectors in India and Japan.

4.1.4 Rules

Authorities encourage hosts to implement house rules to ensure guests have a smooth accommodation experience without disturbing the residential neighbourhood. House rules can be included in the “Additional notes” section of the Airbnb account’s listing details. Guests appreciate it when the host informs them of the hosts’ expectations upfront.

Noise

Guests use Airbnb for a variety of reasons, including holidays and festivities. To provide a smoother experience, hosts can inform guests about how noise affects neighbours early on.

The host can reduce excessive noise in a variety of ways:

· Establishing a quiet hours policy.

· Not allowing pets.

· Indicating whether the listing is appropriate or not for children or infants.

· Prohibiting parties and additional unregistered guests.

Parking

Ensure that guests are aware of any parking restrictions in the building and surrounding area.

Some examples of prospective parking rules are:

· “Only park in a designated area.”

· “Due to street cleaning on Tuesdays and Thursdays, avoid parking on the west side of the street.”

· “Street parking is allowed from 7 pm to 7 am.”

Pets

In a rental or multi-family residential structure, the host should first verify the lease or building guidelines to ensure that pets are not prohibited. If guests are allowed to bring pets, they will prefer to know where they may exercise their pets and dispose of waste. If a guest’s pet annoys the neighbours, the host needs to have a backup plan, such as the contact number of the local pet kennel.

Smoking

If the host does not allow smoking for guests, it is recommended that signs be posted to warn guests. If it is permitted, make sure there are ashtrays in appropriate areas.

Neighbours

The host should be considerate of their neighbours. The neighbourhood is vital not only for the host but also for the guests. Therefore, it is advised to discuss with the neighbours and obtain their feedback about the plans to start hosting and the thoughts on preparation and measures that will be taken to mitigate any potential adverse effects on them.

Roommates

If a potential host currently shares a home with roommates or housemates, the host might consider creating a formal agreement with the housemates to set expectations. Housemate agreements might cover topics such as how often you expect to host, guest conduct, revenue sharing, and more.

4.1.5 Safe

The host needs to thoroughly inspect their home and identify any spots where guests might trip or fall, then either remove the hazard or clearly mark it. They must repair any exposed wires and verify that the stairs are safe and equipped with handrails. Furthermore, any objects that may be dangerous to the guests should be removed or locked up by the host.

The host must assure that the home is child-safe or inform guests of any potential concerns. Some guests travel with young children and need to know if the residence is appropriate for them. The “Additional notes section” of the Listing details in the Airbnb account can be used by the host to warn potential risks or that the place is not suited for children and infants.

The host is responsible for ensuring that the home is appropriately ventilated and that the temperature controls are clearly marked and working. In addition, the host must guarantee that guests understand how to use the air conditioning system safely. If the residence has gas appliances, the host should ensure that the carbon monoxide detector is working and that the appliances are repaired regularly. The host should also follow any gas safety rules that apply to the home. The host must also establish safe occupancy limitations based on local government requirements.

4.1.6 Insurance

Hosts are covered by Airbnb’s Host Guarantee and Host Protection Insurance for specific damages and liabilities. However, legal regulations may still require hosts to have homeowner’s insurance, renter’s insurance, or enough liability coverage. Other insurance requirements may apply to hosts as well. In most cases, hosts must consult with an insurance agent or carrier to ensure that their homeowners or renters policy provides enough liability coverage and property protection for their listings. For example, in New South Wales, hosts must hold insurance that covers liability for third-party injuries and death.

4.1.7 Restrictions

The host must guarantee that all necessary licences, permits, zoning, safety, and health standards are followed, including any local business administration licence requirements. In addition, if the property has a mortgage or other type of loan pledged against it, the host should verify whether there are any restrictions on subletting or hosting. For example, in Singapore, renting private residential properties for less than three consecutive months is prohibited to the same person as governed by the Planning Act.

Subletting and hosting are sometimes prohibited by leases, contracts, building regulations, and community rules. Therefore, the host must review any contracts they have signed or contact their landlord, community council, or other appropriate body. For instance, if the host is a tenant in Dubai, obtaining a “No Objection Certificate” from the landlord is mandatory.

Subletting without permission is frequently prohibited in social housing or subsidised housing. Therefore, if the host lives in a social housing community and wants to become a host, they should contact the appropriate housing authority or housing association. For example, in Singapore, to rent out public housing units, it is mandatory to obtain written approval from the Housing and Development Board (HDB) and other restrictions, including a minimum rental period of six months and who may rent to.

4.1.8 Obligations

In several countries, hosts are obliged to report guest details to relevant authorities once they check in to the property. For example, when accommodation is provided for a foreigner in Thailand, the property owner must notify the Immigration Bureau or the local Immigration Offices within 24 hours. Hosts in both India and China have to follow a similar procedure. In addition, countries like French Polynesia, where it is not mandatory to obtain a license to offer accommodation services, still require hosts to report their rental activity to the relevant authority.

4.1.9 Tax

Tax obligations of hosts can be varied depending on specific conditions. Therefore, hosts are advised to research their tax obligations or obtain the services of a qualified tax professional. Generally, money earned as an Airbnb host is considered taxable income and may be subject to various taxes such as rental tax, income tax, or VAT. For example, in Thailand, if a host’s income exceeds Baht 1.8 million or more per year, have to register as a VAT operator. In addition, the income received from hosting is subjected to personal income tax at progressive rates up to 35%.

4.1.10 Priority Areas

As per the literature review, there are three basic approaches to regulating Airbnb: “outright prohibition, laissez-faire approach, and limiting Airbnb with some constraints” (Guttentag, 2015; Jefferson-Jones, 2015; Miller, 2014). Among the regulatory responses of countries the study analysed, the majority have adopted “limiting Airbnb with some constraints”. Constraints include mandatory registration and licensing, insurance requirements, recording and reporting guest information and necessary provisions for guest privacy, code of conduct, emergency contact details, fire safety, roommates, neighbourhood concerns, noise, pets, smoking, parking and Covid 19 precautions. Additionally, these constraints can be identified as “qualitative constraints” in regulating Airbnb and similar sharing accommodation platforms (Nieuwland & van Melik, 2020). French Polynesia has adopted a laissez-faire approach but must declare any tourism accommodation activity with the Tourism Department of Tahiti, French Polynesia. On the other hand, Singapore could be identified as a country with strict regulations and almost fall into the category of countries that have adopted the “outright prohibition approach”. In Singapore, it is prohibited to rent private residential properties for less than three consecutive months to the same person as governed by the Planning Act.

Based on the analysis, 18 priority areas were identified to be focused on in introducing regulations and guidelines for informal tourist accommodations driven by sharing accommodation platforms. Namely,

- Registration and licensing

- Taxation of Airbnb income

- Provisions for required general quality and service standards and hygiene condition

- Data and information-sharing agreements with the Airbnb platform

- Recording and reporting guest Information

- Provisions for misbehaviour or malpractices

- Provisions for guest privacy

- Provisions for code of conduct, emergency contact details

- Provisions for insurance

- Provisions for fire safety

- Provisions for house rules

- Provisions for roommates

- Provisions for neighbourhood concerns

- Provisions regarding noise

- Provisions for pets

- Provisions for smoking

- Provisions for parking

- Provisions for Covid 19 precautions

4.2 Regulation of Peer-to-Peer Accommodation Industry in Sri Lanka

The official government institution responsible for regularizing the tourism industry in Sri Lanka is the Sri Lanka Tourism Development Authority (SLTDA). According to the Tourism Act, No. 38 of 2005, all institutions engaged in tourist accommodation must register under Sri Lanka Tourism Development Authority (SLTDA). As per the SLTDA statistics, there are only 1,367 registered tourist accommodation service providers. However, there are around 26,162 registered Airbnb listings in Sri Lanka. The number of Airbnb Listings is higher than the number of SLTDA registered tourist accommodation establishments in every district of Sri Lanka. The establishments that provide accommodation for tourists in Sri Lanka can be divided into three broad categories: “Tourist Hotels, Supplementary Establishments, and Other Establishments”. Tourist Hotels include “Classified Tourist Hotels, Boutique Hotels and Unclassified Tourist Hotels. Supplementary establishments consist of “Boutique Villas, Guest Houses, Rest Houses, Home Stay Units, Tourist Bungalows, Rented Tourist Homes, Rented Tourist Apartments and Heritage Bungalows/Homes”. Other establishments are those that have not been officially registered with the Sri Lanka Tourism Development Authority.

Even though the SLTDA has identified the growing importance of Airbnb and similar short term rental platforms in their strategic plan, still there are no explicit rules or regulations governing these accommodation establishments. However, SLTDA has already recognized peer-to-peer accommodations offered through Airbnb under supplementary establishments. For example, in Sri Lanka, most Airbnb rentals are “Private Room” rentals, and there are a significant number of “Shared Room” rentals. The guest shares the accommodation space with the host and host’s family in both above listing types. This resembles the “Homestay” concept, which is already recognized and regulated by the SLTDA. Whereas “Rented Homes and Apartments” resembles entire place listings where guests enjoy the whole accommodation space without the hosts’ presence. SLTDA is practising a rigorous process in registering accommodation service establishments and renewing the licenses to ensure the quality and service standard for a positive hospitality experience. However, a large portion of peer-to-peer accommodation establishments has remained unregulated. For example, there are only 548 homestay units that have been registered under SLTDA. However, there are around 16,830 combined Private and Shared Room listings within the Airbnb Platform. Interviews with Airbnb hosts revealed that hosts are reluctant to get registered under SLTDA due to unawareness and lack of enforcement of regulations by the SLTDA.

In a separate study, the analysis of Airbnb guest reviews in Sri Lanka highlighted significant issues in some Airbnb units’ accommodation quality and standard. Therefore, to ensure a positive tourism experience for guests, an appropriate level of regulation has become a necessity. The existing regulations on homestay units, bungalows, rented homes, and apartments seem to be lacking in several areas, as identified by reviewing regulations and policies on short term rentals in other Asia Pacific countries.

As mentioned earlier, in Sri Lanka, it is mandatory to register and obtain a license from SLTDA to engage in the hospitality business, and the license must be renewed annually. Furthermore, provisions for ensuring general quality and service standards and hygiene conditions have been well recognized in the existing regulations and guidelines. In terms of educating and making guests aware of the code of conduct and emergency contact details seems to be lacking. There is also a gap in provisions for guest privacy, neighbourhood concerns, roommates, noise, pets, smoking and insurance requirements (Table 04). The SLTDA has yet to recognize the impact and importance of peer-to-peer or sharing accommodation platforms in updating rules, regulations and guidelines for Homestay Units, Bungalows, Rented Homes and Apartments.

Table 04. Existing regulations and guidelines for Homestay Units, Bungalows, Rented Homes and Apartments

|

Australia |

China |

French Polynesia |

Hong Kong (SAR) |

India |

Japan |

New Zealand |

Singapore |

South Korea |

Thailand |

UAE (Dubai) |

Sri Lanka |

|

|

Registration and licensing |

ü |

ü |

ü* |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

|

Taxation of Airbnb income |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

|

|

|

Provisions for required general quality and service standards and hygiene condition |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

|

Data and information sharing agreements with the Airbnb platform |

ü |

ü |

ü |

|

||||||||

|

ü |

ü |

ü |

|

ü |

||||||||

|

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

|

ü |

|||

|

Provisions for guest privacy |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

|

Provisions for code of conduct, emergency contact details |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

|

|

Provisions for insurance |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

|

|

Provisions for fire safety |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

|

Provisions for house rules |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

|

|

Provisions for roommates |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

|

|

Provisions for neighbourhood concerns |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

|

|

Provisions regarding noise |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

|

|

Provisions for pets |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

|

|

Provisions for smoking |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

|

|

Provisions for parking |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

|

Provisions for Covid 19 precautions |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

ü |

Source: Compiled by the Author

* Registration only. No license requirements.

5 CONCLUSION

The rise of online peer-to-peer accommodation sharing platforms driven by Airbnb allowed millions of individuals worldwide to offer their private residential space to strangers. The increasing demand for peer-to-peer accommodations, which was first portrayed as tourists being less expensive and more authentic than traditional tourist accommodation, resulted in significant structural changes in destinations worldwide. Therefore, Peer-to-Peer or Sharing Accommodation has been extensively researched in various domains. However, this novel phenomenon has fascinated most researchers while presenting various challenges for policymakers.

Theoretically, the study contributes to the existing body of knowledge on regulating short-term rentals and the ongoing discussion on whether and how governments should regulate them by offering a systematic classification of peer-to-peer accommodation laws and regulations in several Asia Pacific cities and countries. According to the study, Asia Pacific countries have tight rules regarding short-term rentals, which need permits, specific safety procedures, and information supply. Even with tight rules in place, countries want to promote Airbnb’s beneficial economic impacts on the tourism and hospitality industry at large, including local micro-entrepreneurs, while minimising its negative consequences. Except for Singapore, where short-term rentals under six months are illegal, which pretty much bans the use of accommodation for tourist accommodation. Prevailing regulations and guidelines of most countries and cities have been more focused on property conditions, emergency response, privacy, fire safety, neighbourhood, house rules, noise, parking, pets, smoking, and insurance requirements. The study also compares the existing regulations and guidelines of Sri Lanka with policy actions taken by other Asia-Pacific nations. The current policies and guidelines in Sri Lanka do not explicitly focus on Airbnb or any short-term rental platforms. However, existing legislation must be modified to address discovered flaws to provide a positive tourist experience.

Practically, the study provides valuable insights on policy responses undertaken by several Asia Pacific countries, which would help policymakers who are planning to introduce legal measures to regulate short term rental platforms. The study also reveals the existing deficiencies in the Sri Lankan policy response towards this phenomenon to introduce appropriate measures for a sustainable tourism industry. Existing and potential Airbnb hosts may find this study helpful in planning their accommodation business by adhering to widely accepted standards and guidelines to avoid potential risks associated with the business.

This study is certain to have significant limitations, which may have impacted the findings in some way. Because the study focused on cities and nations in the Asia Pacific, including Sri Lanka, the results’ application in other locations may differ due to geographical variables. Due to time constraints, the study was confined to a few cities and countries in the Asia Pacific. As a result, more qualitative in-depth case studies of regulatory approaches may be conducted in other North and South American, African cities and countries, allowing for comparisons across cities and countries, leading to more general conclusions. Since enforcement remains a challenge, further research on the impacts of regulatory measures and enforcement methods is needed. Furthermore, most regions have just recently implemented short-term rental laws, and there is little research on the regulations’ implications.

6 FUNDING AND ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This study was supported by the Research Grant awarded by the University of Sri Jayewardenepura (ASP/RE/MGT/01/2018/48) and the Center for Real Estate Studies (CRES), University of Sri Jayewardenepura.

7 CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors certify that they have no affiliations with or involvement in any organisation or entity with any financial or non-financial interest in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.

8 REFERENCES

Airbnb. (2021). About Us. Airbnb Newsroom. https://news.airbnb.com/about-us/

Airey, D., & Chong, K. (2011). Tourism in China. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203820346

Amaro, S., Andreu, L., & Huang, S. (2018). Millenials’ intentions to book on Airbnb. Current Issues in Tourism. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2018.1448368

Arias Sans, A., & Quaglieri Domínguez, A. (2016). Unravelling Airbnb: Urban Perspecives from Barcelona. Reinventing the Local in Tourism: Producing, Consuming and Negotiating Place, 209–228. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781845415709-015

Biber, E., Light, S. E., Ruhl, J. B., & Salzman, J. (2017). Regulating business innovation as policy disruption: From the model t to airbnb. Vanderbilt Law Review, 70(5), 1561–1626. https://vanderbiltlawreview.org/lawreview/2017/10/regulating-business-innovation-as-policy-disruption-from-the-model-t-to-airbnb/

Brochado, A., Troilo, M., & Shah, A. (2017). Airbnb customer experience: Evidence of convergence across three countries. Annals of Tourism Research, 63, 210–212. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2017.01.001

Bryman, A., & Burgess, R. (1999). Qualitative Research. SAGE Publications Ltd. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446263150

Burtch, G., Carnahan, S., & Greenwood, B. N. (2018). Can you gig it? an empirical examination of the gig economy and entrepreneurial activity. Management Science, March, 5497–5520. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2017.2916

Cramer, J., & Krueger, A. B. (2016). Disruptive Change in the Taxi Business: The Case of Uber. American Economic Review, 106(5), 177–182. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.p20161002

Curry, D. (2021). Airbnb Revenue and Usage Statistics (2021). Business of Apps. https://www.businessofapps.com/data/airbnb-statistics/

Dann, D., Teubner, T., & Weinhardt, C. (2019). Poster child and guinea pig – insights from a structured literature review on Airbnb. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 31(1), 427–473. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-03-2018-0186

Dolnicar, S. (2019). A review of research into paid online peer-to-peer accommodation: Launching the Annals of Tourism Research Curated Collection on peer-to-peer accommodation. Annals of Tourism Research, 75, 248–264. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2019.02.003

Duuren, E. van, Zee, E. van der, & Hee, V. van. (2017). Airbnb en stedelijk toerisme in Utrecht. Geografie, 26(1), 1–9. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/314142320_Airbnb_en_stedelijk_toerisme_in_Utrecht

Edelman, B. G., & Geradin, D. (2015a). Efficiencies and Regulatory Shortcuts: How Should We Regulate Companies like Airbnb and Uber? SSRN, 1–33. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2658603

Edelman, B. G., & Geradin, D. (2015b). Efficiencies and Regulatory Shortcuts: How Should We Regulate Companies like Airbnb and Uber? SSRN Electronic Journal, 293–328. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2658603

Edelman, B., Luca, M., & Svirsky, D. (2017). Racial Discrimination in the Sharing Economy: Evidence from a Field Experiment. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 9(2), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1257/app.20160213

Espinosa, T. P. (2016). The Cost of Sharing and the Common Law: How to Address the Negative Externalities of Home-Sharing. Chapman Law Review, 19(2), 597–627. http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=lgs&AN=117415506&site=ehost-live

Finck, M., & Ranchordas, S. (2016). Sharing and the City. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2741575

Füller, H., & Michel, B. (2014). “Stop Being a Tourist!” New Dynamics of Urban Tourism in Berlin-Kreuzberg. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 38(4), 1304–1318. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12124

Gallagher, L. (2017). The Airbnb Story: How Three Ordinary Guys Disrupted an Industry, Made Billions and Created Plenty of Controversy (1st editio). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Miththapala, S. S., & Tam, S. (2017). Impact of online travel operators on SME accommodation providers in Sigiriya, Habarana, Dambulla-Opinion.

Ellepola, Y. (2017). Policy research institutions and the health SDGs: building momentum in South Asia-Sri Lanka country report.

Gant, A. C. (2015). Tourism and commercial gentrification. International Conference on “The Ideal City: Between Myth and Reality. Representations, Policies, Contradictions and Challenges for Tomorrow’s Urban Life,” 27–29.

Gotham, K. F. (2005). Tourism Gentrification: The Case of New Orleans’ Vieux Carre (French Quarter). Urban Studies, 42(7), 1099–1121. https://doi.org/10.1080/00420980500120881

Gottlieb, C. (2013). Residential Short-Term Rentals: Should Local Governments Regulate the “Industry”? Planning and Environmental Law, 65(2), 4–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/15480755.2013.766496

Grimmer, L., Massey, M., & Vorobjovas-Pinta, O. (2018). Airbnb is blamed for Tasmania’s housing affordability problems, but it’s actually helping small businesses. He Conversation AU. https://theconversation.com/airbnb-is-blamed-for-tasmanias-housing-affordability-problems-but-its-actually-helping-small-businesses-91566

Grimmer, L., Vorobjovas-Pinta, O., & Massey, M. (2019). Regulating, then deregulating Airbnb: The unique case of Tasmania (Australia). Annals of Tourism Research, 75, 304–307. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2019.01.012

Gurran, N., & Phibbs, P. (2017). When Tourists Move In: How Should Urban Planners Respond to Airbnb? Journal of the American Planning Association, 83(1), 80–92. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944363.2016.1249011

Guttentag, D. (2015). Airbnb: disruptive innovation and the rise of an informal tourism accommodation sector. Current Issues in Tourism, 18(12), 1192–1217. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2013.827159

Guttentag, D. A., & Smith, S. L. J. (2017). Assessing Airbnb as a disruptive innovation relative to hotelsSubstitution and comparative performance expectations. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 64, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2017.02.003

Han, H. (2021). Consumer behavior and environmental sustainability in tourism and hospitality: A review of theories, concepts, and latest research. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 29(7), 1021-1042. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2021.1903019

Holm, A. (2016). Berlin: How is Airbnb changing the housing market? A political economy of vacation homes. Gentrification Blog News to Strengthen District Mobilization and Tenant Struggles. https://gentrificationblog.wordpress.com/2016/07/05/berliin-wie-veraendert-airbnb-den-wohnungsmarkt-eine-politische-oekonomie-der-ferienwohnungen/

Holman, N., Mossa, A., & Pani, E. (2018). Planning, value(s) and the market: An analytic for “what comes next?” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 50(3), 608–626. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X17749730

Jefferson-Jones, J. (2015). Airbnb and the Housing Segment of the Modern “Sharing Economy”: Are Short-Term Rental Restrictions an Unconstitutional Taking? Hastings Constitutional Law Quarterly, 42(3), 557–575.

Kaplan, R. A., & Nadler, M. L. (2015). Airbnb: A case study in occupancy regulation and taxation. The University of Chicago Law Review Dialogue, 82, 103–115. http://heinonline.org/hol-cgi-bin/get_pdf.cgi?handle=hein.journals/uchidial82§ion=8

Koopman, C., Mitchell, M. D., & Thierer, A. D. (2015a). The Sharing Economy: Issues Facing Platforms, Participants, and Regulators. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2610875

Koopman, C., Mitchell, M., & Thierer, A. (2015b). The Sharing Economy and Consumer Protection Regulation: The Case for Policy Change. The Journal of Business, Entrepreneurship & the Law, 8(2), 530–540. https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1130&context=jbel

Krippendorff, K. (2018). Content Analysis An Introduction to Its Methodology (4th Editio). SAGE Publications, Inc.

Lee, Y.-J. A., Jang, S., & Kim, J. (2020). Tourism clusters and peer-to-peer accommodation. Annals of Tourism Research, 83, 102960. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2020.102960

Leismann, K., Schmitt, M., Rohn, H., & Baedeker, C. (2013). Collaborative Consumption: Towards a Resource-Saving Consumption Culture. Resources, 2(3), 184–203. https://doi.org/10.3390/resources2030184

Lines, G. E. (2016). Regulating Airbnb in the New Age of Arizona Vacation Rentals. Arizona Law Review, 57, 1163–1182. http://arizonalawreview.org/pdf/57-4/57arizlrev1163.pdf

Maitland, R. (2010). Everyday life as a creative experience in cities. International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research, 4(3), 176–185. https://doi.org/10.1108/17506181011067574

Miller, S. R. (2014). Transferable Sharing Rights: A Theoretical Model for Regulating Airbnb and the Short-Term Rental Market. SSRN Electronic Journal, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2514178

Molly, C., & Arun, S. (2017). Self-Regulation and Innovation in the Peer-to-Peer Sharing Economy. University of Chicago Law Review Online, 82(1 (8)), 1–18. https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1039&context=uclrev_online

Moylan, A. (2016). Roomscore 2016: short-term rental regulation in u.s. cities. 55, 1–12. https://www.rstreet.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/RSTREET55.pdf

Nieuwland, S., & van Melik, R. (2020). Regulating Airbnb: how cities deal with perceived negative externalities of short-term rentals. Current Issues in Tourism, 23(7), 811–825. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2018.1504899

O’Sullivan, F. (2018). Barcelona Finds a Way to Control Its Airbnb Market. Bloomberg CityLab. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2018-06-06/how-barcelona-is-limiting-airbnb-rentals

Oskam, J., & Boswijk, A. (2016). Airbnb: the future of networked hospitality businesses. Journal of Tourism Futures, 2(1), 22–42. https://doi.org/10.1108/JTF-11-2015-0048

Ranchordás, S. (2015). Does sharing mean caring : regulating innovation in the sharing economy Does Sharing Mean Caring ? Regulating Innovation in the Sharing Economy. Minnesota Journal of Law, Science & Technology, 16(1), 413–476. https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1356&context=mjlst

Rauch, D. E., & Schleicher, D. (2015). Like Uber, But for Local Governmental Policy: The Future of Local Regulation of the “Sharing Economy.” SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2549919

Schor, J. (2016). DEBATING THE SHARING ECONOMY. Journal of Self-Governance and Management Economics, 4(3), 7. https://doi.org/10.22381/JSME4320161

Sheppard, S., & Udell, A. (2016). Do Airbnb properties affect house prices? Working Paper.

Stevenson, H. H. (1983). Perspective on Entrepreneurship. Harvard Business School.

Sundararajan, A. (2014). The Power of Connection: Peer-to-Peer Businesses. In Peer-to-Peer Businesses and the Sharing (Collaborative) Economy: Overview, Economic Effects and Regulatory Issues Arun.

Thierer, A. D., Koopman, C., Hobson, A., & Kuiper, C. (2015). How the Internet, the Sharing Economy, and Reputational Feedback Mechanisms Solve the “Lemons Problem.” SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2610255

Van Holm, E. J. (2020). Evaluating the impact of short-term rental regulations on Airbnb in New Orleans. Cities, 104(March), 102803. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2020.102803

Von der Heidt, T., Muschter, S., Caldicott, R., & Che, D. (2020). Airbnb in the Byron Shire, Australia – bane or blessing? International Journal of Tourism Cities, 6(1), 53–71. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJTC-04-2019-0056

Wang, D., & Nicolau, J. L. (2017). Price determinants of sharing economy based accommodation rental: A study of listings from 33 cities on Airbnb.com. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 62, 120–131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2016.12.007

Wegmann, J., & Jiao, J. (2017). Taming Airbnb: Toward guiding principles for local regulation of urban vacation rentals based on empirical results from five US cities. Land Use Policy, 69(May), 494–501. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2017.09.025

Zervas, G., Proserpio, D., & Byers, J. W. (2017). The Rise of the Sharing Economy: Estimating the Impact of Airbnb on the Hotel Industry. Journal of Marketing Research, 54(5), 687–705. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmr.15.0204

DECLARATION OF CONTRIBUTIONS TO THE ARTICLE - CREdiT

|

ROLE |

Lasika |

Terance |

Nishani |

Ariyawansa |

|

Conceptualization – Ideas; formulation or evolution of overarching research goals and aims. |

x |

|

|

|

|

Data curation – Management activities to annotate (produce metadata), scrub data and maintain research data (including software code, where it is necessary for interpreting the data itself) for initial use and later re-use. |

x |

|

|

|

|

Formal analysis – Application of statistical, mathematical, computational, or other formal techniques to analyze or synthesize study data. |

x |

|

|

|

|

Funding acquisition - Acquisition of the financial support for the project leading to this publication. |

|

|

|

x |

|

Investigation – Conducting a research and investigation process, specifically performing the experiments, or data/evidence collection. |

x |

|

|

|

|

Methodology – Development or design of methodology; creation of models. |

x |

|

|

|

|

Project administration – Management and coordination responsibility for the research activity planning and execution. |

x |

|

|

|

|

Resources – Provision of study materials, reagents, materials, patients, laboratory samples, animals, instrumentation, computing resources, or other analysis tools. |

x |

|

|

|

|

Software – Programming, software development; designing computer programs; implementation of the computer code and supporting algorithms; testing of existing code components. |

x |

|

|

|

|

Supervision – Oversight and leadership responsibility for the research activity planning and execution, including mentorship external to the core team. |

|

|

x |

x |

|

Validation – Verification, whether as a part of the activity or separate, of the overall replication/reproducibility of results/experiments and other research outputs. |

|

x |

|

|

|

Visualization – Preparation, creation and/or presentation of the published work, specifically visualization/data presentation. |

x |

|

|

|

|

Writing – original draft – Preparation, creation and/or presentation of the published work, specifically writing the initial draft (including substantive translation). |

x |

|

|

|

|

Writing – review & editing – Preparation, creation and/or presentation of the published work by those from the original research group, specifically critical review, commentary or revision – including pre- or post-publication stages. |

x |

x |

x |

x |