1. INTRODUCTION

The history of the beginnings of Rio de Janeiro city located on the disappeared Morro do Castelo is unique and still remains, in a way, unexplored in some of its facets. The countless existing references about this original nucleus of Rio are inscribed in the scope of historiography and literature, in the reproduction of facts in the printed media and in the extensive iconographic and photographic sources. The possibility to represent the city in Morro do Castelo and its slopes as a graphic report emerges with relevance at this moment when the suppression of the hill completes 100 years. The objective of this study is to contribute with the historiography of Rio de Janeiro through the construction of unpublished visual representations based on the story by Machado de Assis: “One for Another” from 1897.

The symbolic meaning of the extinction of the hill ended up demonstrating the protagonism and historical importance of this “geographic and urban piece” in the city of Rio de Janeiro, whose narrative is also indebted to more research and investigation. Therefore, this work is justified by proposing drawing as an analysis tool for the construction of new visual representations of Morro do Castelo, which make the articulation between historical mapping and the literary narratives about the city possible, mediated by digital graphic representation in the construction of the image of the city center between the middle of the century 19th and the early 20th.

Researchers from the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ) in Laboratory of Urban Analysis and Digital Representation (LAURD) have been developing digital urban models for downtown Rio since the 1990s. In addition, previous doctoral thesis (Vilas Boas, 2007) delivered two important documents: a digital model on the morphological structure of Morro do Castelo and surroundings in the historical moment right before of its dismantling in 1921-22; and also cartographic work on the further urbanization of Esplanada do Castelo that appeared in its place. Nowadays, the digital models of LAURD also support other studies, such as the “Literary Guide of Rio de Janeiro'' (Paraízo, Mechler e Silva, 2020), which aims to geolocate literary excerpts about the city in the first decades of the 20th century - moment of physical and social transformation of the city given the intense nationalist “campaign” of this period.

Therefore, these outlined studies mentioned above addresses the contents and works on digital reconstruction of Morro do Castelo and became the forefront of use of digital cartography and models in the urban historiography of Rio de Janeiro. In this sense, this study was used to develop unprecedented drawings of urban scenarios described in the aforementioned text by Machado de Assis. More recently, LAURD´s team participated in the evaluation process of the “Narrativas do Rio'' platform promoted by Rice University, whose objective was to expand the use of the ImagineRio application <https://imaginerio.org/#pr>. In this context, a subgroup was formed, instigated by the idea of composing its own and comprehensive investigation of the Morro do Castelo and its surroundings, considering literature as a source of investigation, having produced two narratives about the Castelo (Andreatta, 2021 and Mechler et al, 2021).

In the city´s historiograph, comprehensive research is present in the book exclusively dedicated to it: “Era uma Vez o Morro do Castelo” (Once upon a time Morro do Castelo) (Nonato and Santos, 2000), initiated by professionals from IPHAN, the preservation body of the historical heritage of the country. Authors José Antonio Nonato and Nubia Melhem Santos promoted an edition that compiles literary, historical and journalistic documents and a plethora of photographs and iconography that highlight the urban and historical importance of Portuguese urbanization in Rio de Janeiro.

In the last two decades, other significant studies and articles were published. It is important to mention some of them such as that of Carlos Kessel “Tesouros do morro do Castelo: Mistério e história nos subterrâneos do Rio de Janeiro” (Treasures of Morro do Castelo: Mystery and history in the underground of Rio de Janeiro) (Kessel, 1997) and, more recently, that of Rebeca Grilo de Sousa, “Os escombros do Castelo: as representações sobre um desmonte em três atos” (The ruins of the Castle: representations of a dismantling in three acts) (Sousa, 2019).

Indeed, the interest in showing the history of Morro do Castelo to a wider audience prompted newspapers to produce an infographic using digital media that clearly highlight the aspect of the hill and its surroundings between 1921 and 1924 (Alvin, 2021). Furthermore, Morro do Castelo was shown in cinema, through the director's documentary "O Desmonte de Monte" (The Dismantling of Monte) Sinai Sganzerla from 2018, or even the artistic performance "Visita a uma Paisagem Desconhecida" (Visit to an Unknown Landscape) by Ismael Monticelli, from 2019. All manifestations demonstrate a clear persistence of the hill’s memory in the city's imagination (Vilas Boas, 2019).

On the other hand, Machado de Assis' work has been exhaustively analyzed and presents itself as a broad and inexhaustible source for understanding the social and physical scenarios of Rio de Janeiro (Jordão, 2015; Petraglia, 2017; Godoi, 2018; Martins, 2020) from the Second Reign until the advent of the Republic. There are various sources of research on this author, however, deserve citation an interesting literary course promoted by Alfredo Pujol (1865-1930) in 1917 when seven conferences on Machado de Assis took place at the Society of Artistic Culture of São Paulo (Martins 2001). The historical review of Machado de Assis' work is produced through publications such as “O Viajante Imóvel” (The Immobile Traveler), a book by Luciano Trigo (Trigo, 2001) and many others outside the academic sphere, such as the documentary “O Rio de Machado de Assis” (Rio by Machado de Assis) in video, by Norma Bengel and Leila Grynberg made in 2001.

In the field of Digital Humanities, also noteworthy is the ambitious project of the Fundação Casa de Rui Barbosa: "Edição dos contos de Machado de Assis como hipertexto" (Editing Machado de Assis's short stories as hypertext) developed by the researcher Marta de Senna, where all of Machado de Assis's fiction (his novels and short stories) can be found in a specific portal <www.machadodeassis.net>, with explanatory links of literary and historical-cultural references, as well as notes on places in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil and the world: commercial stores, cafes, theaters, etc.

In order to characterize the relationship between literature and the city of Rio de Janeiro, Pechman (2002) made a “tour through the authors” of the mid-nineteenth century and observes the relationship between literature and the city of Rio de Janeiro: “in the perception (of the authors) the process of transforming the concrete city into an aesthetic (narrative) fact takes place, and therefore the transformation of the city into an image of the city”. And also:

“It is in Machado de Assis that the issue of “urbanity” reaches a paroxysm (...) Rejecting the romance of customs, Machado de Assis was able, avoiding tropical exuberance, to embrace the urban Brazil that was already defining itself. Entirely “city and carioca”, Machado de Assis, however, escapes the “tourist mentality”, a risk always run by our men of letters” (Pechman, 2002, p. 209).

As is well known, Rio de Janeiro in the second half of the 19th century witnessed a great population growth and physical transformation as a result of the implementation and extension of urban services (drinking water, sewage, public lighting, landscaping of parks, lines and trams, railroad, gas, new buildings, etc.). Transformations that reached their peak, particularly with the reforms promoted at the beginning of the 20th century by Rodrigues Alves and Pereira Passos (Abreu, 1997; Andreatta, 2006, p.175) and which were developed by successive mayors until the removal of the hill.

During the period of change in the Brazilian political condition, from a monarchic to a republican regime, different objectives were given to the city, including the need to erase the colonial aspect and promote the integration of Rio into the “civilized world”. And, in this case, the presence of the “city on Morro do Castelo” meant the existence of the undesirable “colonial stronghold” (Silva, 2003; Lohanne, 2020; Galarce and Linares, 2020). In fact, the historical background demonstrates the validity of the theories of hygienist doctors who for more than half a century announced the need to suppress the hill, ideas that interested some businessmen. The justification for a work of such scale was based on issues of aeration of the dense colonial city, the need for ventilation provided by the sea breezes that were impeded by the “geographic accident”. It is not surprising, therefore, that Morro do Castelo and its inhabitants were becoming entrenched, relegated to oblivion in public policies for urban improvements and beautification of this habitat.

As a result, the “city on the hill” was excluded from the official image that was beginning to be created to project Rio de Janeiro to the world. Perhaps due to this fact, photographers, designers, painters and artists were less interested in portraying him as they sought to promote a new image of cosmopolitan Rio in other environments, namely: Praça XV, Outeiro da Glória, Arcos da Lapa, Praia Vermelha and Urca, the Sugar Loaf cable car, Botafogo, Corcovado and Copacabana, which emerged as the new urban icons of Rio de Janeiro (Martins, 2000).

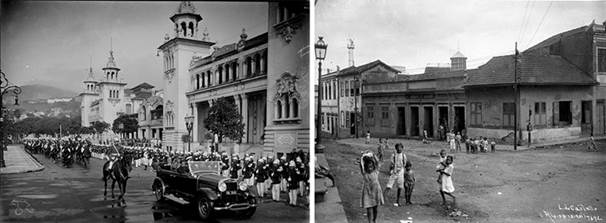

Figs. 1 e 2. The contrast between two worlds that existed in the center of Rio de Janeiro in the beginning of the 1920s: a parade in the Exhibition of the Centenary (Sebastião Lacerda – IMS collection) and a view of Morro do Castelo (Augusto Malta).

Therefore, the contrast between the existence of the “colonial hill”, old, depleted vis a vis the new urban condition of the city renewed, beautified and cosmopolitan reached its apex with the unbridled motive of eliminating it (Figs. 1, 2). There were several reasons for this, one of them coming from the legacy of the medical-hygienist precepts of the 19th century that advocated the need for aeration in the city. In the early 1920s, it was predicted that the landfill by the sea would guarantee the installation of the 1922 International Exhibition and its emblematic pavilions. But the most well-founded hypothesis lies, certainly, in the process of capital accumulation that the city was going through based on the transformation of the land and the generation of its value. However, this is another story of the city of Rio de Janeiro that will not be developed here.

In summary, exploring the visual dimension in Machado de Assis' literary texts means understanding Rio de Janeiro in the mid-19th century and the beginning of the 20th century, in its daily life, observing the social and urban experience that was beginning to conform to a city which was rapidly transforming and aspired to “civilize itself”.

2. REPRESENTATION METHODOLOGY AS A MEAN TO UNDERSTAND THE CITIES

The theory on the representation of cities comes from different formulators, among which the renowned Kevin Lynch (Lynch, 1960), Steen Eiler Rasmussen (Rasmussen, 1951), Rob Krier (Krier, 1979), Aldo Rossi (Rossi, 1966), Amos Rapoport (Rapoport, 1977) and others (Oliveira Capela and Ramirez-Marquez, 2019; Samogorov and Zubkova, 2020; Huang et al., 2021) who, from the 1950s onwards, influenced the development of studies on the perception of cities, their architectures and urban environment (Sokołowicz and Przygodzki, 2020; Abusaada, and Elshater, 2021). However, Brazilian researcher José Barki should be thanked for developing this theme with brilliance and breadth in the careful text of the doctoral thesis “O risco e a invenção: um estudo sobre as notações gráficas de concepção no projeto” (Risk and invention: a study on graphic design notations in the project) (Barki, 2003).

Evidently, the possibility of representing the “city on the hill” from archaeological remains does not apply to this case. The removal of the “Morro do Castelo” and the consequent eviction of the remains of buildings and land to form landfills over the Guanabara Bay made it impossible to carry out any work in this area. Therefore, the documentary sources found in maps, drawings, paintings, photographs and in literature constitute the basis of any urban research for the reconstruction of the image of the hill.

Furthermore, the effort made by the areas of architecture and urbanism to understand the processes that intercede in the interaction of the individual with the built environment was developed in search of common denominators that would serve as a basis for this understanding. According to Barki,

"Some authors consider that occupation — use of spaces and construction of places by individuals — is based on certain 'constants' that could be identified through the study of environmental perception. Authors such as Lynch, Alexander and Boudon are perhaps more in tune with a structuralist view, whereas authors such as Norberg-Schulz and Cousin seek these 'constants' through a phenomenological approach” (Barki, 2003, p. 34).

If on the one hand Lynch became better known when he published “A Imagem da Cidade” (The Image of the City) in 1960, focusing his studies on North American cities, the other authors mentioned above addressed the urban characteristics of European cities or of classical antiquity, in anthropological aspects and sociological. However, Lynch's urban analysis methodology formed the basis of the numerous works that have been developed since then in various universities around the world. Attention was drawn to the importance of recognizing the “image of the city” in its “elements” such as paths, borders, neighborhoods, nodes and physical and/or environmental structures. Elements that structure the "quality of form" observed by its uniqueness, simplicity, continuity, predominance and visual reach.

On the other hand, Steer Eiler Rasmussen, a Danish professor, published his book Towns and Buildings described in drawings and words in 1951, and in the following year the English edition, but these were restricted to the European scope. Although Rasmussen was mentioned by Barki as a “seminal study and little used in professional practice by architects '', it should be noted that this comment is now outdated. In 2014, the Department of Architectural Composition of the Technical School of Architecture in Madrid republished Rasmusssem's book in Spanish, adding a prologue by Profesor Manuel Blanco and an interesting epilogue “Aprender a Pensar. El dibujo como herramienta de análisis” (Learning how to Think. Design as an Analysis Tool) by investigating Professor José Antonio Flores Soto gaining notoriety among academic circles for its relevance and up-to-dateness. According to the latter, “El estudiante de arquitectura actual debería estar atento al mensaje de Rasmussen sobre el dibujo como herramienta de pensamiento" (Rasmussen, 2014, p. 239).

It is interesting to analyze in Krier (1979) the greater importance given to the meaning of the traditional urban space that, according to him, was lost in the modern city. The definition of the concept of "Urban Space '' in Krier is based on the principle that space is delimited by geometric characteristics that derive in aesthetic qualities, allowing for the external perception of spaces. From three basic spatial forms (square, circular and triangular) he created schematic matrices and described the “modular factors '' for understanding the streets, squares and various spaces affected by their angles, segmentations, distortions, etc. Schematic drawings, isometric perspectives in pencil or ink became fundamental in the elucidative schemes for the project to rebuild the center of Stuttgart and served as an example of careful planning in the reconstruction of the post-war city.

Chiavari (1994) in the article “New Look, New Technology: the principle of Modernity” (Chiavari and Grinberg, 1994) begins the text inferring that “drawing is not just a means to reproduce ideas and intentions” and attributes its usefulness and effectiveness as “it plays an autonomous role capable of creating a symbolic mediating and interpreting environment of the relationship with reality”.

If architecture and cities circumscribed in their natural landscape signify the transformation introduced by man to adapt to his needs, the representation of these takes place through the eyes and hands of man. So what is the difference between photography and drawing if they describe the same object? The aforementioned José Antonio Flores Soto offers as an answer that the difference lies in the synthesis exercise required in the construction of each type of image. “El diseño requiere el esfuerzo de captar la realidad y traducirla a líneas, lo cual no es inmediato” but, on the other hand, referring to photography: “Una fotografía, pese a parecer instantánea, realmente requiere un tiempo previo de pensamiento porque no hay ingenuidad en la mirada” (Rasmussen, 2014, p. 240).

The great difficulty in establishing a common theoretical framework that reconciles these reference studies is because the drawings proposed here were simulated from existing photographs and images and are part of an exercise of imagination for the representation of the city described by the writer Machado de Assis, that is, re-imagined by the authors of this article.

When observing the differences between digital drawings in relation to original ones by designers, painters and photographers, it is necessary to remember that they were able to carry out their work from "participatory observation", given that they had the opportunity to visit the Morro do Castelo and produce images to naked eye, enjoying places where points of view fit the needs and/or criteria related to real or even fictitious intentions. José Barki's study (Barki, 2003) is of fundamental importance for this article because it contains an understanding of the history of “graphic notations” from antiquity to the present day, where the development of computer drawings reached the paroxysm of digital techniques.

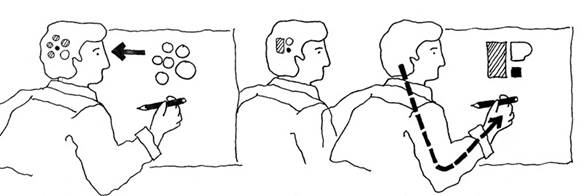

The world of images analyzed as a visual representation is presented in two domains, a concept defined by Santaella and Nöth (2020). The first of them, the signs, represent our visual environment: drawings, paintings, prints, photographs and cinematographic/cinematography, television, holo and infographic images; and the second, immaterial domain of our mind images represent visions, fantasies, imagination, schemes, models or, in general, as mental representations (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. According to Paul Laseau, “graphic thinking” is the creative cycle that is established through the practice of drawing, which opens the path to explorations and discoveries in the Architecture field (Laseau, 1989).

Both domains of the image do not exist separately, as they are already inextricably linked in their genesis. There are no images as visual representations that do not arise from images in the minds of those who produced them, just as there are no mental images that do not have some origin in the concrete world of visual objects.

The discussion that is of interest in this article, therefore, is the issue of the “essence of the drawing” produced in the context of showing views of the city on Morro do Castelo, in which scenes attributed to certain places and characters suggested by the literary author appear. Although it is not possible to prove the facts graphically speaking, secondary information allowed the approach and preparation of digital drawings that offer precision and quality, as will be explained below. In conclusion, in line with the title of the article, we once again quote Barki:

“In general, representation is a notion that is defined, most of the time, by an analogy with vision and with the act of having an image of something. However, it could be used to refer to: the apprehension by the awareness of an object or situation actually present; to the reproduction in consciousness of past perceptions; or, identified with the imagination, it is the anticipation of future events based on the free association of past perceptions” (Barki, 2003, p. 36).

3. DIGITAL RECONSTRUCTION OF MORRO DO CASTELO: CARTHOGRAPHIES AND METHODS

The reconstitution of the look of Machado de Assis' characters is structured from the articulation of different document sources with digital urban models from the center of Rio de Janeiro developed by LAURD, whose origins date back to the 1990s, when the laboratory's first research focused on the colonial city and the need to represent it. In this pioneering experience, in addition to the representation of various historic buildings, the complex digital modeling of the city's topography was also highlighted, characteristic of its landscape inseparable from its historical processes of urban transformation.

In the early 2000s, these first digital models were reorganized and systematized with reference to Eduardo Canabrava’s important historical atlas (Canabrava, 1964). Its boundaries of representation cover the entire central area comprised of the four historic hills - Morros do Castelo, Santo Antônio, São Bento and Conceição - extending towards the interior of the territory and unfolding into a series of planks that represent the area at different moments since the 17th century, containing information about various elements of the territory - natural accidents, streets and buildings – through time.

From the three-dimensionalization of these maps, where a series of information about the city from other documents were added, specific studies on certain areas started to demand a detailing of parts of the model that would allow a closer look at the object. In this process, the doctoral thesis on Morro do Castelo (Vilas Boas, 2007), the Master's thesis on Morro de Santo Antônio (Bueno, 2013), the study on Largo de São Francisco (Vilas Boas, 2018) and, currently in progress, the study on the Agache Plan, are examples that reveal the versatility of these bases to study the dynamics of city transformation through digital graphic representation, in the sense recommended by Roberto Segre, one of the founders of LAURD. According to him,

“the essential objective of the research studies is to develop a reading of the city that seeks to reveal, deepen and clarify the complexity of the urban structure; the elements that define it, in its particularity, identity and meanings, revealed in the three-dimensional, versatile, non-linear vision of coincidences or temporal divergences that digital graphics make possible” (Segre, 2014).

We understand digital urban models as a space for research development, a place for synthesizing and transforming documentary information into three-dimensional information, where its limits of original representation are significantly expanded. However, there are obstacles in the way: as new documents are incorporated into the model of a given urban context, more divergences between them will appear, even though they may be documents made at the same time, they will hardly be documents produced synchronously. Furthermore, every representation of a city is an act of interpretation and, therefore, like every interpretation, socially associated with the point of view of those who produce it (Chartier, 2002), which implies the notion of the uniqueness of each source and the difference among them as basic characteristics of a documental set.

Therefore, it is in the gaps formed by differences that research through digital modeling takes place in its essence, as it implies the positioning of the researcher in making representational decisions, a process that will also transform the digital urban model into a historiographical document. As the model is improved, other avenues of exploration open up based on the possibility of closer viewing, and from other points of view, certain aspects of the city. According to Denise Pinheiro Machado and José Kós,

“also, in the field of historical research, it can be highlighted, in recent works on investigation methods, approaches to the consequences of the reconstruction of buildings and urban sets in three dimensions in the formulation of hypotheses (...) that representations in two dimensions do not could foresee” (Pinheiro Machado and Kós, 2003).

In this context, the digital urban model that represents Morro do Castelo in the early 1920s, detailed for the development of the doctoral thesis mentioned above, was used to graphically represent the points of view of the characters Josino and Pia, from the short story “Uma por Outra” originally published in 1897 by Machado de Assis, recreated from the model that represents the spatial relationships that existed in the places described by the author. Thus, when observing the points of view of his characters, new fields of interpretation open up, revealing other dimensions of the work of Machado de Assis.

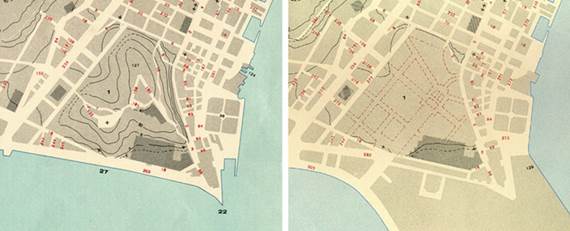

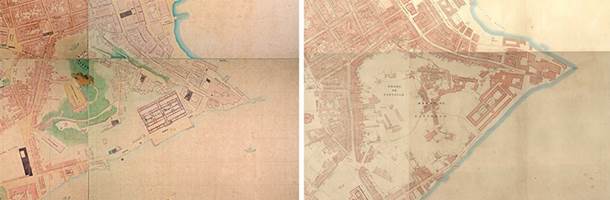

The documentary bases represented by Eduardo Canabrava's atlas are the starting point of the digital urban models used in this study (Fig. 4). Its various boards provide important information for understanding the transformation of the territory over four centuries, but they do not present enough detail to allow an approximation of the view of the city: the topography is not precisely drawn, nor can we see aspects related to the buildings, as only streets are represented.

Fig. 4. Representations of Morro do Castelo in 1910 and the Esplanada do Castelo in 1928, after its dismantling, according to the historical atlas of Eduardo Canabrava (Canabrava, 1964).

Significant elements (natural accidents, streets, buildings etc.) are identified by graphic symbols and by numbers that identify them on the various boards, which allows the mapping of elements over time, a characteristic that makes it a document of great historiographical interest, insofar as it is concerned with representing the temporality of the city. Although not graphically detailed, this characteristic makes the atlas an important source for digital modeling, as its concern with the representation of time is also a guiding approach for research conducted by the laboratory.

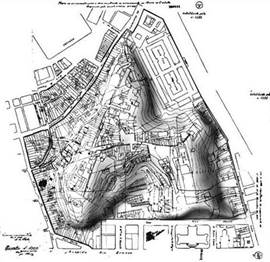

Fig. 5. Information about Morro do Castelo in the Alignment Project give the conditions for its 3d digital modeling. (Naylor Vilas Boas / LAURD).

For more detailed studies, the information contained in the "Alignment Projects" constitute a valuable source for the study of urban development in Rio de Janeiro from the first decade of the twentieth century, revealing through their drawings the dynamic, conflicting and contradictory process of the formation of the city. Established from the urban reforms of Pereira Passos, they aimed to represent the urban changes planned for certain stretches defined by the decree that accompanied them. They had the force of law. Many were executed, many others were not put into practice. In certain cases, many Alignment Projects were edited in a short period of time for the same place, as was the case of the projects for the Esplanada do Castelo published throughout the 1920s (Vilas Boas, 2007), which clearly demonstrates the lack of planning and consensus on the occupation of the area gained during and a few years after the demolition of Morro do Castelo.

The primary document that structured the modeling of the hill is the first in this series of projects dealing with the area, the Alignment Project n. 1355, published August 17, 1920 (Fig. 5). It records an initial intention to occupy the site, with the definition of some blocks drawn on a detailed topographical and cadastral survey of Morro do Castelo. The articulation of information in this document with aerial photographs (Fig. 6) taken in the same period (Vianna, 2001) provided the basic subsidies for the digital modeling of that urban historical context, where individual recognition of the streets and buildings on the hill and its surroundings is possible, understood through the streets of Misericórdia, Santa Luzia, São José and Avenida Central.

Fig. 6. Aerial photography of a part of Misericórdia neighborhood in the vicinities of Morro do Castelo (Vianna, 2001).

Once structured on an urban scale (Vilas Boas, 2010), closer approximations of the look of the model become possible, which leads to the need to deepen the levels of detail by inserting new documents into the process. At this level of approximation, attention turns to public spaces and the buildings to which they are related, which in most cases requires the contribution, in documentary terms, of photographs taken at street level with a closer approximation to the studied place. Like any document, photographs also have their limits of representation, which can be expanded as other photographs are collated, not without bringing with them their own coincidences and contradictions. Recent research (Gomes, 2020) has been proposing ingenious solutions to automate this document analysis process, detecting the most photographed areas of a given urban context from a given set of photographs, generating what researchers call a documental “reliability map” of a place.

Fig. 7. Morro do Castelo in the maps of Leopoldo José da Silva (Silva, 1870) and Edward Gotto (Gotto, 1871).

In a recent research front, the information contained in the Alignment Project n. 1355, which makes it possible to identify the addresses of the Morro do Castelo, paved the way for the insertion of data related to the population that lived there. Information from primary textual sources extracted from police incidents recorded by the local police station between 1916 and 1922, initially explored in a master's thesis (Paixão, 2008), contains a valuable historical database that identifies hundreds of local residents, containing not only their addresses, but also other characteristics, such as ethnicity, age, profession, among others. In articulation with other primary documents, it becomes possible to advance towards a humanization of the reconstruction of Morro do Castelo, as those people can be identified and visualized in their places of residence. In this sense, the digital model starts to represent not only the urban morphology, but also becomes a place of graphic representation of its residents, giving them their deserved historical visibility.

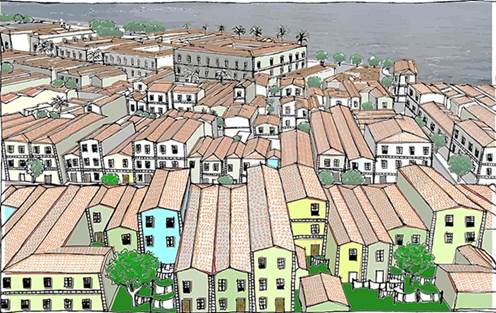

Efforts are also being made to vectorize maps describing the city in the 1870s (Fig. 7), an initial methodological step in the digital modeling process of the city in this decade. From this time, two maps stand out for their detailed description of the central area: the maps by Leopoldo José da Silva (Silva, 1870) and Edward Gotto (Gotto, 1871), which graphically represent the city in a very similar way, detailing it to accurately scale their lots and buildings. Even though they were produced almost simultaneously, they present some important differences in the design of certain blocks around Morro do Castelo, which will imply the need for the input of other documents to make representation decisions.

The existence of a third and peculiar map (Fig. 8) that represents the city in the same decade, capable of adding fundamental information for its three-dimensionalization, defines an interesting set of documents to be used as a starting point for this process. The “Architectural Map of the City of Rio de Janeiro”, edited in 1874 and reedited in 1971 (Fragoso, 1874), is concerned with graphically representing the facades of the buildings, drawn over the blocks on the city map. By representing the appearance of its facades and the heights of the buildings through them, this map contributes with/to information that defines the basic conditions necessary for the three-dimensional representation of the city in the 1870s.

Fig. 8. Part of rua da Misericórdia in the “Mappa Architectural do Rio de Janeiro” (Fragoso, 1874).

Like the digital urban model of the 1920s, the 1870s model of downtown Rio will establish a new digital space of study, which represents the city at a time marked by the pressures of urban growth on a context that is still largely colonial, which gave rise to the first projects that think of the city in its urban logic (Andreatta, 2006; Rabha, 2008), whose ideas were only put into practice by the next generation, in the first decades of the 20th century.

4. THE STORY “ONE FOR ANOTHER”: GLANCES IN THE SLOPES OF MORRO DO CASTELO

As already noted, Machado de Assis is a writer deeply identified with Rio de Janeiro, a city that lived intensely in the second half of the 19th century. Through his work, one comes into contact with a city undergoing rapid transformation that little by little surpasses its colonial structures. Its characters frequently transit the city and, through them, a new relationship with the public space that was constituted throughout the century is evidenced, typical of a bourgeois society that was consolidated, when the street became the meeting place, of seeing and the being seen, whose main centrality, in Machado's time, was Rua do Ouvidor.

His narratives have a strong visual dimension, and his gaze moves through the urban space through his characters, introducing the city to the reader's imagination. There are many presences of Rio in his work, whether in the description of its streets, buildings or its daily life, as we can see in one of Counselor Aires' wanderings, from the novel “Memorial de Aires” (Aires Memorial), published in 1908:

“Today, coming home from the city, I passed this one, and found myself in Largo do Machado, when the tram stopped. I got off and before setting off I stopped for a moment and walked through the garden, towards the Matriz da Glória, looking at the façade of the temple with the tower on top.” (Assis, 1994c).

In addition to this urban dimension, the look of her characters - what their eyes see and say - are themes present in her literary explorations, which were able to create one of the most memorable characters in Brazilian literature in the figure of Capitu with her eyes "like an oblique and covert gypsy woman”, in the novel “Dom Casmurro”, published in 1899 (Assis, 1994a). Let's stay with the impressions and emotions of Bentinho's gaze on her:

“I was all eyes and heart, a heart that this time was sure to come out of my mouth. She couldn't take her eyes off that fourteen-year-old creature, tall and strong and full, snuggled into a half-faded calico dress. Her thick hair, done in two braids, with the ends tied together, in the fashion of the time, flowed down her back. Brunette, clear and large eyes, straight and long nose, she had a thin mouth and a wide chin." (Assis, 1994a).

Therefore, we situate our approach at the intersection between these two important categories in Machado de Assis' work - the city and the gaze -, as we explore the possibilities of graphic representation of his narratives, with methods and instruments capable of reconstructing the perspectives of his characters in the urban space, revealing other ways of interpreting his work.

In the story “Uma por Outra” (One for Another), Machado de Assis (1994d) reaches us through the reminiscences of Josino, a character who recalls his time as a medical student living in Rio de Janeiro, around the 1860s, when he then lived in an attic on the old Rua da Misericórdia. Now missing, this street was adjacent to one of the slopes of Morro do Castelo and structured the neighborhood of the same name, being the main connection between Largo do Paço (now Praça XV de Novembro) and Largo and Ladeira da Misericórdia, one of the accesses to the hill. One of the oldest streets in Rio de Janeiro, its appearance was not very different from other streets in the central area: a long compact corridor defined on both sides by two-story houses, usually with the presence of commerce on the ground floor and rooms on the upper floors (Fig. 9). A street with plenty of urban life, although subject to the rigors of its antiquity. In the words of the chronicler João do Rio,

Fig. 9. Rua da Misericórdia, 1928. (Augusto Malta / Brasiliana Fotográfica).

“It was the first street in Rio. We all departed from it, in it passed the rogue viceroys, the greedy, the naked slaves, the lords in hammocks; in it the filth flourished, in it the flower of the Jesuit influence unbuttoned. (...) But, battered sob, the first effort of a number of unhappy people, it continued throughout the centuries, always regrettable, and so anguished and frank and true in its pain that flattering patriots and governments, no one, no one ever remembered to take it from that silent prayer, that old beggar's cry: — Mercy!" (Rio, 2007).

Josino lives the city intensely as a student, circulates with friends in cafes and theaters, where he has the opportunity to see and be seen. In these environments, he interacts with the local society, notices the women and in his thoughts he gives them fictitious names. The attic, where he lives on Rua da Misericórdia, faces the Morro do Castelo. One day, he notices the figure of a woman in the window of a house on the hill, which he calls "Pia", and soon establishes a relationship with her shape that will feed his fantasies, as he begins to believe that she too looked at him. Josino's description of this moment reveals the importance of looking at Machado de Assis, who masterfully narrates the complex and ambiguous visual relationships that are established from the character's vision, where part of the story will be built:

“My attic overlooked Morro do Castelo. In one of those houses climbing disorderly up the hill, I saw the shape of a woman, but I only guessed that it was because of her dress. From far away, and a little below, he couldn't make out the features. He was used to seeing women in the other houses on the hill, like on the roofs of Rua da Misericórdia, where some came to lay out the clothes they were washing. None attracted me more than an instant of curiosity. What was it about that one that held my attention the longest? I take that, first of all, my state of loving vocation (...). Then - and this could be the main cause - because the girl I am dealing with seemed to be looking at me from a distance, standing in the dark background of the window." (Assis, 1994d).

The text provides us with some clues to speculate where Josino's attic on Rua da Misericórdia would be located, considering a priori its location on the side of the street whose back faces the hill. According to his narrative, he is distant enough for the silhouette of “Pia” to stand out in his visual field but, at the same time, not so close as to allow facial recognition. From this point onwards, the digital model becomes an adequate means for exploring some hypotheses, as it enables a three-dimensional visualization of the urban context in which the narrative takes place. Once the probable location of Josino's attic is identified, it becomes possible to simulate the look of the characters and graphically represent their points of view.

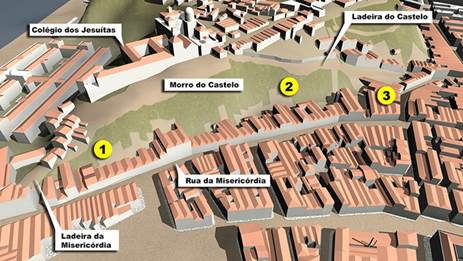

Fig. 10. Representation of Rua da Misericórdia and the Morro do Castelo through the digital urban model (Naylor Vilas Boas / LAURD).

Considering the image of the digital model that represents Rua da Misericórdia and Morro do Castelo (Fig. 10), we can see that there are three sections where the houses on the street and the hill were more directly related. The first stretch (1) was located in the initial part of the street, next to the Church of N. Sra. de Bonsucesso, to Largo and to Ladeira da Misericórdia, one of the accesses to the hill. It was a short and steep climb, ending in a long square, flanked by the former Colégio dos Jesuítas, the Church of Santo Inácio, the observatory and from where you had a wide view of the Guanabara Bay. In the initial stretch of the slope, the backside of some buildings turned towards the houses on Rua da Misericórdia, which put them as a possibile location of Josino's attic. However, through the model we can observe that the distance between the houses in that section was not large (about 30m), and this distance would possibly allow visual contact with “Pia” without further ambiguity.

After this initial area, the presence of the old Jesuit complex on the hill meant that a long stretch of Rua da Misericórdia turned towards it. From the back windows of these houses, you could see the monumental presence of that architectural ensemble that for almost four centuries of its history marked the city's landscape. Only from the middle of the street onwards the backs of the houses turned back to the houses on the hill and, at this point (2), the hypothesis of locating Josino's attic there becomes more consistent, as the distance between them (about 70m) becomes plausible with the visual relationships narrated in the story, and the alignment between them would favor the formation of an image in the window with sufficient visual strength to be perceived.

The last stretch of the street (3) that relates to the hill is its meeting with Rua do Cotovelo which, in turn, led to the beginning of the climb of the Morro do Castelo, another access to the hill. Through the model, we can infer that the distance between the back of the houses on Rua da Misericórdia and those located on the slope (about 45m) makes the narrative plausible for that place. However, its facades did not face directly onto Rua da Misericórdia, as they adapted to the topography of the slope. Despite the adequate distance, the skewed view of these houses would not favor the perception of a figure in the window that would catch Josino's attention. Therefore, we consider that the middle section of the street (2) meets the conditions for us to locate Josino's attic there.

Fig. 11. Josino´s point of view (Litza Passos / LAURD).

Through its window (Fig. 11), we can imagine the view of the lower part of the slope, with some vegetation or grass and, a little further up, the hillside of the Castle cutting the hill, with the constant rise and fall of the population - a daily routine also visited by Machado in the novel “Esau and Jacó”, from 1904, when he narrates the ascent of the hill by the sisters Natividade and Perpétua (Assis, 1994b). Up the slope, Josino would see the slope going up a little more until his gaze found the houses situated at the top of the hill, on Rua do Castelo, which back sides faced the Misericórdia neighborhood. At this moment, his eyes would see the windows of these houses and, in one of them, the mysterious figure of “Pia”. Behind the houses, perhaps he noticed the top of some palm trees on the hill. And in the background, the sky.

Fig. 12. Pia´s point of view (Anna Clara de Oliveira / LAURD).

Let us now investigate the gaze of “Pia” (Fig. 12): if she leaned towards and looked down from her window, perhaps out of her immediate field of vision, she would see the Castelo slope, with people going up and down. Beyond it, further down, you would also see a little of the hillside and soon after, your field of vision would open up to the entire Misericórdia neighborhood and the expanse of Guanabara Bay. She would see roofs and many windows, dozens of them, of the houses that stretched practically to the edge of the bay. We can imagine that, from her point of view, Josino's attic window was one more among many others, part of the wide landscape that unfolded. Probably his figure would not easily stand out amongst so many other elements of her field of view, which contributes to the idea that everything is nothing more than Josino’s fantasy, who also notices the situation and reveals his concerns:

“This time, just when I couldn't distinguish the girl's features, nor she mine, the /courtship was firmer and continued. Maybe that's why. Vagueness is is very important in such affairs; the unknown attracts more. So days and weeks passed. We already had certain hours, special days when contemplation was longer. I, after the first few days, feared that there was a mistake on my part, that is, that the girl would look at another attic, or simply at the sea." (Assis, 1994d).

5. CONCLUSION

In this article, we demonstrate the horizons that open up as different fields of knowledge are mediated through digital graphic representation, in an interdisciplinary approach that seeks to articulate Urban History and Literature through cartographic and literary representations that speak to us of Rio de Janeiro in the second half of the 19th century. In this process of reconstruction of this city, digital urban models present themselves as a space for historiographical investigation and constitute in themselves an important research document. Furthermore, they represent an open field for expanding studies on the interpretation of urban space and for the representation of the design of past cities by digital means.

The use of digital models in the simulation from the point of view of Machado de Assis' characters is in line with LAURD´s recent interest in the theme of Literature and the City, which is also revealed in other recent approaches conducted in the laboratory (Paraízo et al, 2020). In this sense, the development of the digital models is presented as a path for studies that can deepen the writer's work and his relationship with the city, in order to enable him to approach the eyes of his characters through graphic representation.

Immediate developments in this research are related to the novel “Esaú e Jacó”, previously mentioned, where in the first chapter Machado de Assis tells us about the ascent of the characters Natividade and Perpétua to Morro do Castelo in 1871, at the same time as the story “Uma por Outra” (One for Another). Although he doesn't tell us from which slope they climbed the hill, his narrative describes a socially alive and diverse environment, in descriptions with great imagery force, points of view that can also be reconstructed through the digital model:

“Natividade and Perpétua knew other parts, besides Botafogo, but Morro do Castelo, no matter how much they heard about it and the cabocla who reigned there in 1871, was as strange and remote to them as the club. “The steep, the uneven, the poorly wedged slope mortified the feet of the two poor ladies. Nevertheless, they continued to climb, as if they were penitent, slowly, faces down, veils down. The morning brought some movement; women, men, children who went down or up, washerwomen and soldiers, some employee, some shopkeeper, some priest, everyone looked at them in amazement (...)." (Assis, 1994b).

Therefore, the research should focus on deepening the work of Machado de Assis, seeking to identify other potentially interesting narratives to be represented. In another development, a specific area of the city can be read from many authors. In this sense, the interest also turns to Misericórdia street itself, already mentioned by João do Rio in this text, and which is probably the subject of many other authors to be investigated. It is well documented from an iconographic and cadastral point of view, which will allow a significant approach to the look of its urban spaces and its architecture. Its importance to the city's history - and its disappearance - makes it present as a necessary object of study as part of the preservation of the city's memory and heritage.

6. ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

We would like to thank the team formed by professors, undergraduates, masters and doctoral researchers who are part of LAURD, and who together constitute an important space for discussion and research on the urban history of Rio de Janeiro and on digital graphic representation.

Being part of the research team under the guidance of Prof. Naylor Vilas Boas, whose central theme is digital models and Morro do Castelo, we specifically thank the authors of the illustrations presented here, undergraduate students Anna Clara Oliveira, Litza Passos and Yasmim Moura Fernandes. Their engagement with the work was fundamental for the development of the research and for the results achieved so far.

7. REFERENCES

Abreu, M. de. (1997). Evolução Urbana do Rio de Janeiro (3o ed). IPLANRIO.

Abusaada, H., & Elshater, A. (2021). Competitiveness, distinctiveness and singularity in urban design: A systematic review and framework for smart cities. Sustainable Cities and Society, 102782. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2021.102782

Andreatta, V. (2006). Cidades Quadradas, Paraísos Circulares. Mauad.

Andreatta, V. (2021). A vida do estudante Josino no Rio de Janeiro do séc. XIX. Interpretação da obra “Uma por Outra” de Machado de Assis – 1897. https://narratives.imaginerio.org/view/600b0120c405e1001898850c.

Assis, M. de. (1994a). Dom Casmurro. In Obra Completa. Nova Aguilar.

Assis, M. de. (1994b). Esaú e Jacó. In Obra Completa. Nova Aguilar.

Assis, M. de. (1994c). Memorial de Aires. In Obra Completa. Nova Aguilar.

Assis, M. de. (1994d). Uma por Outra. Paraula.

Barki, J. (2003). O Risco e a Invenção: Um Estudo sobre as Notações Gráficas de Concepção no Projeto [Doutorado]. Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro.

Bueno, R. (2013). Globos Virtuais e Cidade: Leituras Gráficas sobre a História do Morro de Santo Antônio no Rio de Janeiro [Mestrado]. PROURB/FAU/UFRJ.

Canabrava, E. (1964). Atlas da Evolução Histórica do Rio de Janeiro. Instituto Histórico e Geográfico Brasileiro (IHGB).

Chartier, R. (2002). A História Cultural: Entre Práticas e Representações (2o ed). Difel.

Chiavari, M. P., & Grinberg, P. E. (1994). A paisagem desenhada: O Rio de Pereira Passos. Centro Cultural Banco do Brasil.

Fragoso, J. R. (1874). Mappa architectural da cidade do Rio de Janeiro [Map]. P. Robin.

Galarce, F. E., & Linares, F. (2020). Cartografias [des] veladas: situações de residualidade urbana. O caso do Morro do Castelo. RUA, 26(1). https://doi.org/10.20396/rua.v26i1.8660216

Godoi, R. C. D. (2018). "Cá está a criadinha!": uma análise da imitação hoje avental, amanhã luva de machado de assis (1860). Machado de Assis em Linha, 11, 54-70. https://doi.org/10.1590/1983-6821201811234

Gomes, E. B. O., Araújo, T. S. L., Aflalo, A.-B. B., & Ferraz, A. S. P. (2020). Digital reconstruction of historical heritage—A quantitative methodology for measuring the reliability of Largo de Nazaré iconographic data between the years 1900 and 1910. Transformative Design. Sigradi 2020 - XXIV International Conference of the Iberoamerican Society of Digital Graphics, Medellín, Colombia. https://doi.org/10.5151/sigradi2020-11

Gotto, E. (1871). Plan of the city of Rio de Janeiro [Map].

Huang, J., Obracht-Prondzynska, H., Kamrowska-Zaluska, D., Sun, Y., & Li, L. (2021). The image of the City on social media: A comparative study using “Big Data” and “Small Data” methods in the Tri-City Region in Poland. Landscape and Urban Planning, 206, 103977. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2020.103977

Jordão, R. P. (2015). O Valongo de Machado na cartografia do Rio de Janeiro: a escravidão em cena na cidade. Machado de Assis em Linha, 8, 99-113. https://doi.org/10.1590/1983-682120158166

Kessel, C. (1997). Os Tesouros do Morro do Castelo: Ouro dos Jesuítas no Imaginário do Rio de Janeiro. Revista de História Regional, 2(2), 09–50.

Krier, R. (1979). Urban Space (1o ed). Rizzoli.

Laseau, P. (1989). Graphic Thinking for Architects and Designers. John Wiley & Sons.

Lohanne, L. G. (2020). Turismo, cartografia e imagem: os significados dos mapas e a construção de narrativas sobre os espaços turísticos do Rio de Janeiro. Cadernos de Geografia, (41), 105-118. https://doi.org/10.14195/0871-1623_41_8

Lynch, K. (1960). The Image of the City (1o ed). The MIT Press.

Martins, A. L. (2020). Critérios bibliográficos para atribuição de textos a machado de assis: análise do ensaio “a imprensa na atualidade” (1860). Machado de Assis em Linha, 13, 62-78. https://doi.org/10.1590/1983-6821202013295

Martins, C. (Org.). (2000). A Paisagem Carioca. Prefeitura da Cidade do Rio de Janeiro / RioArte.

Martins, W. (2001). História da inteligência brasileira: 1915-1933. 2 (Vol. 6). Queiroz Editora.

Mechler, C., Silva, M. A., & Paim, R. (2021). O Subterrâneo do Morro do Castelo. Narrativas do Rio. https://narratives.imaginerio.org/view/600eb057c405e1001898852c

Nonato, J. A., & Santos, N. M. (Orgs.). (2000). Era uma Vez o Morro do Castelo. IPHAN.

Oliveira Capela, F., & Ramirez-Marquez, J. E. (2019). Detecting urban identity perception via newspaper topic modeling. Cities, 93, 72-83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2019.04.009

Paixão, C. M. Q. (2008). O Rio de Janeiro e o Morro do Castelo: Populares, Estratégias de Vida e Hierarquias Sociais (1904-1922) [Mestrado, Universidade Federal Fluminense].

Paraízo, R. C., Mechler, C., & Silva, M. A. (2020). Rio de Janeiro Literary Guide: Strolling Through Short Stories and Newspaper Chronicles In The First Decades of the 20th Century. 8, 541–548.

Pechman, R. M. (2002). Cidades estreitamente vigiadas: O detetive e o urbanista. Casa da Palavra.

Petraglia, B. (2017). O rio de janeiro nas crônicas de a semana. Machado de Assis em Linha, 10, 126-147. https://doi.org/10.1590/1983-6821201710229

Pinheiro Machado, D., & Kós, J. R. (2003). Desafios do urbanismo contemporâneo: Considerações sobre a representação digital nas pesquisas urbanas. In Urbanismo em Questão (p. 304). PROURB.

Rabha, N. M. de C. E. (2008). Planos Urbanos Rio de Janeiro: O Século XIX. IPP.

Rapoport, A. (1977). Human aspects of urban form: Towards a man-environment approach to urban form and design (1o ed). Pergamon Press.

Rasmussen, S. E. (1951). Towns and Buildings Described in Drawings and Words (1o ed). University Press of Liverpool.

Rio, J. (2007). A Alma Encantadora das Ruas (2o ed). Martin Claret.

Rossi, A. (1966). L`Architettura della Città (1o ed). Marsilio Editori.

Samogorov, V. A., & Zubkova, I. I. (2020). City-forming elements of formation of the «collage» image of the city. Urban construction and architecture, 10(3), 164-169. https://doi.org/10.17673/Vestnik.2020.03.20

Santaella, L., & Nöth, W. (2020). Imagem: cognição, semiótica, mídia. Iluminuras.

Segre, R. (2014). Memorial do Laboratório de Análise Urbana e Representação Digital (1995-2011). In Leituras Gráficas da Cidade—Anais do I Seminário LAURD (1o ed, Vol. 1). Rio Books.

Silva, L. (2003). História do Urbanismo no Rio de Janeiro. Administração municipal, Engenharia e Arquitetura dos anos 1920 à Ditadura Vargas. E-papers.

Silva, L. J. da. (1870). Planta da Cidade do Rio de Janeiro [Map].

Sokołowicz, M. E., & Przygodzki, Z. (2020). The value of ambiguous architecture in cities. The concept of a valuation method of 20th century post-socialist train stations. Cities, 104, 102786. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2020.102786

Soto, J. A. F. (2014). Epílogo. In S. E. Rasmussen, Ciudades y Edifícios. Reverté.

Sousa, R. G. de. (2019, março). Os escombros do Castello: As representações sobre um desmonte em três atos. URBANA: Revista Eletrônica do Centro Interdisciplinar de Estudos sobre a Cidade, 10(2), 401–426. https://doi.org/10.20396/urbana.v10i2.8650475

Trigo, L. (2001). O Viajante Imóvel: Machado de Assis e o Rio de Janeiro de Seu Tempo. Record.

Vianna, L. F. (Org.). (2001). Rio de Janeiro: Imagens da Aviação Naval (1916-1923) (M. Boot & R. Boot, Trads.). Argumento.

Vilas Boas, N. (2007). A Esplanada do Castelo: Fragmentos de uma História Urbana [Tese de Doutorado, PROURB/FAU/UFRJ].

Vilas Boas, N. (2010). A Construção de Cidades Digitais: Desafios e Estratégias Metodológicas. Anais do I ENANPARQ. Encontro da Associação Nacional de Pesquisa e Pós-Graduação em Arquitetura e Urbanismo, Rio de Janeiro.

Vilas Boas, N. (2018). Máquina do Tempo Digital. Ciência Hoje, 347.

Vilas Boas, N. (2019). The Dawn of Modernity in Rio de Janeiro: Historiographic Approaches to Digital Mapping the Everyday Life of a Changing City. Digicult: Scientific Journal on Digital Cultures. Digital Art and Humanities for Cultural Heritage [special issue], 4(2), 14. https://doi.org/10.4399/97888255301483

DECLARATION OF CONTRIBUTIONS TO THE ARTICLE - CRediT

|

ROLE |

Verena Andreatta |

Naylor Vilas Boas |

|

Conceptualization – Ideas; formulation or evolution of overarching research goals and aims. |

X |

X |

|

Data curation – Management activities to annotate (produce metadata), scrub data and maintain research data (including software code, where it is necessary for interpreting the data itself) for initial use and later re-use. |

- |

- |

|

Formal analysis – Application of statistical, mathematical, computational, or other formal techniques to analyze or synthesize study data. |

- |

- |

|

Funding acquisition - Acquisition of the financial support for the project leading to this publication. |

- |

- |

|

Investigation – Conducting a research and investigation process, specifically performing the experiments, or data/evidence collection. |

- |

- |

|

Methodology – Development or design of methodology; creation of models. |

- |

X |

|

Project administration – Management and coordination responsibility for the research activity planning and execution. |

X |

X |

|

Resources – Provision of study materials, reagents, materials, patients, laboratory samples, animals, instrumentation, computing resources, or other analysis tools. |

- |

- |

|

Software – Programming, software development; designing computer programs; implementation of the computer code and supporting algorithms; testing of existing code components. |

- |

X |

|

Supervision – Oversight and leadership responsibility for the research activity planning and execution, including mentorship external to the core team. |

- |

- |

|

Validation – Verification, whether as a part of the activity or separate, of the overall replication/reproducibility of results/experiments and other research outputs. |

- |

- |

|

Visualization – Preparation, creation and/or presentation of the published work, specifically visualization/data presentation. |

X |

X |

|

Writing – original draft – Preparation, creation and/or presentation of the published work, specifically writing the initial draft (including substantive translation). |

X |

X |

|

Writing – review & editing – Preparation, creation and/or presentation of the published work by those from the original research group, specifically critical review, commentary or revision – including pre- or post-publication stages. |

X |

X |